There’s no parking space on the road outside of Friel’s Bar.

Cars are lined along the ditches for as far as the eye can see, a classic country road bending and winding but not really committed to a full turn. It’s just green all around you in this part of Ireland. Soft, rain-soaked grass rolls up and down the hills at either side of the long rural drive that’s broken up every so often by the odd pub, maybe a shop here and there and a more regular, re-occuring sight of a giant stadium manning another GAA pitch.

On the road out to the Davitt’s GAA club – that’s the only way you can navigate yourself in this neck of the woods – there’s a turnoff downhill into boggier terrain where someone has created a makeshift car park. It’s filled to capacity.

One of those old-fashioned Defender jeeps is abandoned on the muddy slope at the side of a barn and there’s just about space for a three-door to roll in behind but that closed gate is becoming a concern.

Christ almighty, I never thought I’d have to worry about being clamped in Swatragh.

But they’ve turned out in their numbers tonight in this little village in south county Derry.

Over 400 people are in the marquee outside of Friel’s and they’re all here for one man and for one club.

Shaun Mullan tragically lost his life in November when he was struck on the road whilst on his bike one morning before work. It was only two months after marrying his wife Sinéad. It will remain one of the most harrowing stories that ever swept over the GAA community up north and it hit home with just about every Gael and just about every person hoping and dreaming of ever starting a young family of their own one day.

He was a son, a husband, a team mate, a friend.

My deepest sympathy to the family of the late Shaun Mullan, his wife Sinead and the Gaels of @BallerinGAA and wider community during these saddest of days. pic.twitter.com/ZvEej3q2HB

— Mary K Burke (@MKBurke1) November 21, 2017

So they’ve travelled from all over to be in Swatragh on this Saturday night to remember him and the sight of so many people from so many communities and eras would make your heart swell.

It’s GAA heartland down here where some of the biggest enemies in the country live side by side at such close quarters – a lot of them are so much on top of each other, you wonder how so many clubs could survive at all in such a small area but then that’s the strength of the communities. It’s the stubbornness of them too.

Just eight miles up the road, Shaun’s proud club Ballerin resides. You don’t even think you’re out of Maghera – the Glen club – when you’re told you’re suddenly in Swatragh. Kilrea just seems to be down a back lane there and Slaughtneil’s on the side of the mountain that everyone else is scattered around the foot of. Then Glenullin is planted somewhere in that radius too.

The rivalry is real in Derry. If you wanted to, you could probably find decent reason to hate just about every club in the county because of the intensity of it all. A slap in one game, a row at an underage match, a transfer dispute, an off the field feud, the bad memories of over the top cheers and car horns being rubbed in your face as your neighbours peg on another score – these sort of things can fester until it becomes customary to just hate that crowd down the road or over the ditch. Hate them between the white lines at least.

Not tonight though. Tonight, we’re all just Gaels, regardless of crest. Tonight, we’re all just here for Shaun.

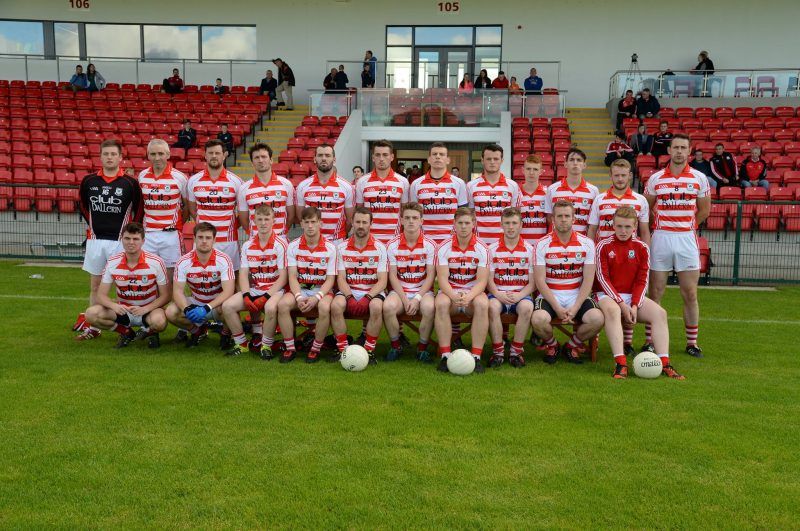

Ballerin is one of those clubs that probably too many footballers in Derry have a thing about. They’re not at the same level as their 1976 Ulster Senior Football Championship winning days but they’re a good intermediate side that could rattle anyone on their day. And they always rattle. Shaun Mullan – Elvis, as they call him – embodied that fearlessness in the team.

I had the misfortune of playing against Shaun on a few occasions and, every single time, I left the field thinking the same thing:

“Why the fuck did I try to shoulder that boy?”

Mullan was made of tougher stuff. He was strong, he was game, he loved the prospect of an upset. And as much as he left his mark all over the poor bodies that were stupid enough to stand anywhere near his vicinity, he really left his mark on the world with such a short space of time.

So Swatragh is covered in black jerseys, in memory of Ballerin’s number nine. They all have his number at the back of their kits and they all read Elvis at the top. Athletic young men – his team mates – are stewarding the whole thing, directing operations, pulling out more chairs, making sure a superstar line-up including Joe Brolly, Owen Mulligan, Brendan Devenney and Joe McMahon are being well looked after. A couple of camogie players are running around hounding people to buy raffle tickets and, for a night, every single person in this marquee is one – even the Tyrone men amongst us.

One by one, bundles of auction items are being carried in, the next one seemingly bigger than the last.

One of the most prominent figures of Derry camogie is at the door sorting out wristbands and it’s only when you step back and look at all this madness unfolding with utter dedication and precise co-ordination that you appreciate this whole thing is simply being held together out of unity.

You see legendary figures of yesteryear laughing with the current senior players. Respected elderly journalists are telling stories and reminding you of who once marked Devenney and who Joe McMahon is cousins with. Lads with a few drinks in their hands are pretending to be upset with a renowned club referee who has long since been off duty and there’s just a nice realisation in the air that games are won and lost but all this goes on at the end of it all.

I’ve the easiest task of the night, just putting questions to such an open goal of a line-up. Get them to recount a few tales of the glory days, they’re all good craic and everyone is interested in them – what could go wrong? That’s until I meet Brolly in the toilets and think I’d better introduce myself if we’re going to be on stage together.

“Alright, Joe, I’m Conán. I’m MCing the thing,” I say in my most friendly voice.

Joe turns and looks at me, thankfully he’s zipped up at this stage.

“You’re fucked.”

And, with that, he walks out.

But it set the tone for the night. Insults being exchanged, stories being topped and no-one trying to do anything else other than make everyone in the room laugh.

In the crowd, you have over 400 people hooked on the every word of these legends of the game and as much as all these communities are together for one family and one club, you’ll soon have Devenney and Mulligan pulling on Ballerin jerseys, you’ll have All-Stars being taken down to size by the character from Dungiven and you’ll have an entire room of equals once more.

The way it always was.

The auction items are a joke.

Signed Leinster jerseys, signed Dublin top, Scott Brown’s Celtic kit, All-Ireland final tickets. Eoin Bradley has donated his cup-winning Coleraine shirt. Big Ruairi Convery – one of the finest hurlers Derry has produced in a long time – has his hand up for a Canning family hurl but the thing goes for over a grand. Item by item is reeled out, Rory McIlroy gear, historic Slaughtneil memorabilia, and people are dipping deeper and deeper into their own pockets to bring the sum total for the night to over €23,000.

All the while, young men are stood up all over the marquee making sure the auctioneer doesn’t miss a raised bid. They’re encouraging people to keep going, keep going for the cause. They’re surveying the room, interrogating others’ half interest out of pure dutiful desperation and every time a fellow GAA person decides to give the guts of a grand of their own money to their efforts, they shake their heads in sheer amazement, put their hands on their faces and offer a little smile to one another that, somewhere along this awful journey, their exhausting endeavours might just be worth something in the end.

It’s way more than they could ever have estimated and it’s a genuine privilege to even just stand in the same room as these people whose work and generosity and restlessness is all going towards the intensive care unit in Belfast – every last penny of it.

They’re heroes, if truth be told. Because of Shaun’s family, because of the work of everyone involved tonight and in this morning’s underage blitz, because of the pure kindness of each and every last soul who’s turned up – even the Tyrone men – lives will be saved and what’s more, a legacy has been honoured.

In all of this, Ballerin have taken the life of a fierce warrior and a big heart and they’ve allowed his mighty affect on the Derry GAA community to transcend way beyond the far too few years he was offered on this earth. They’ve immortalised his character and you can see it in the bravery of every man and woman in this room tonight.

Because of that, Shaun Mullan will never stop inspiring the people of Ballerin.

Where else in the world would you get this?