You see some sights standing on Hill 16.

Tickets for an All-Ireland semi-final seat are priced at 45 quid so the riffraff like me are scrambling for a spot on the terrace.

Derry men don’t get many days out at Croke Park so it’s not the easiest stadium to navigate around for the untrained. Why would anyone, for example, think they’d have to allow 15 minutes to get from the Hogan Stand to the Hill? But that’s the charm of Dublin and that’s the impracticalities of Croker and, if you’re not used to it, they’ll shaft you every time.

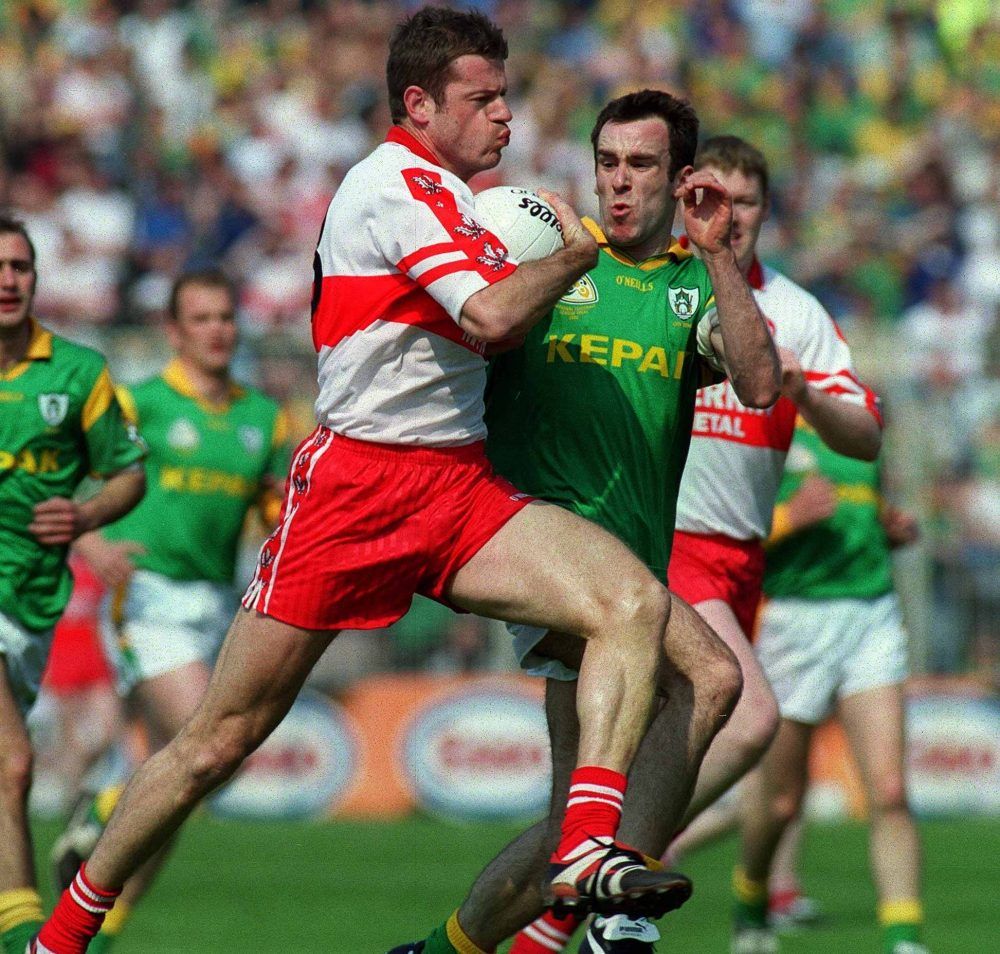

I’ve been fortunate enough over the last few years to get the press box view and, of course, I’ve even been able to splash out for a Canal End seat every so often too but I haven’t stood on Hill 16 since Derry drew with Meath in the league final back in 2000, when half the stadium was still under development and the new Cusack Stand was obstructing the view of a lot of us standing in the corner of the ground.

So we’re running from guard to steward asking for directions between the terraced houses of north Dublin wondering why the fuck we’re going so far away from the stadium to get to its entrance. There are two Tyrone men falling over each other, two fags hanging out of one of their mouths, a straw hat covering the other guy’s face and, when we see they’re headed in the same direction we are, we’re confident we’re on the right path to Hill 16.

There’s only five minutes to throw-in for the senior game and if you hadn’t a watch handy, you could set your clock to the small crowd of Kerry fans walking back up the road in the opposite direction making their way for home after the minor game, presumably having seen enough football for the day.

But minor football isn’t what it was with the change to under-17 – that’s a massive, massive difference at that age – and, Jesus, the real action is only getting started anyway whilst the Kerry folk piss off, probably forcing themselves to be sick to the stomach at the thought of two Ulster teams in one All-Ireland semi-final. And yet the football weekend has been crying out for Monaghan and Tyrone, for a game that would enthral, grip and inspire, one that would be in the balance until the end and one which could, would you believe, serve up some quality play despite players defending.

There are less than 50,000 people in Croke Park but the place is electric. Every catch of a ball brings the Cusack to its feet, every wide is celebrated like a goal and, every time anyone comes within range of scoring, there’s an excited murmur spreading throughout the stadium like the sound of a pile of school kids gathering in uncontrollable nerve at the prospect of two of their class mates fighting each other outside the back gates at 3.30.

There are duels being fought all over these plains. Ryan Wylie is hanging out of Lee Brennan and Drew is patrolling the Monaghan backline like a bouncer on a power-trip, refusing entry for the sake of it, slapping men out of his sight for kicks. Vinny Corey and Mattie Donnelly are taking lumps out of one another through the middle third and Fintan Kelly and Peter Harte are treating the crowd to an exhilarating foot race up and down the pitch.

Hill 16 is like a Red Button option for digital viewers, it has its own sideshow going on. There’s already vomit scattered over the steps, lads are on shoulders, swinging their tops frantically around in the air, and teenagers are doing the rounds during the game, doing laps of the terrace as if they were in a night club, desperate to be seen by the right person. Every chant of ‘Farney Army’ is drowned out by Tyrone’s version of the Wolfe Tones’ Celtic Symphony.

Here we go again

We’re on the road again

We’re on the road again

We’re on our way to Sam again

Every kick of Rory Beggan’s is greeted with a 40 second build up of screams in attempt to put him off but it doesn’t get any less mesmerising watching this year’s best ‘keeper strike his right foot through and across the ball as it backspins perfectly onto the inch of space he’s looking to drop it into.

Any of the players that come near the full forward line are being goaded or encouraged with manic roars and, off the back of those, arguments are spilling out and laughs are being exchanged. There’s a guy standing with a motorbike helmet on. He’s got a long grizzly beard and a cheap pair of those sunglasses that reflect different colours in the sun. He waits every time until he sees the umpire has finished waving a flag for Tyrone until he then lets out an almighty yawp in celebration.

When you look over your shoulder, it’s just pure carnage. There are flares being let off and what seems to be an area designated specifically for moshing only as grown men trample into one another and jump shoulder first into whoever’s beside or in front of them. By the time the second half is starting, there are still guys filtering into the ground for the first time when they were probably in Dublin two and a half hours already but as mad as this drama all is and as much as it’s contributing to the fever pitch – and it really is – it’s too hard to take your eyes off the pitch for too long, especially now that Padraig Hampsey is marshalling Conor McManus right in front of the Hill.

When you’re an underage corner back, coaches – back in the day at least – used to say that you should be able to tell them the colour or your man’s underwear – they’d hardly get away with that today. The idea was simple though, that you should be so close to him that you’d know the intimate details. Padraig Hampsey could probably tell you a bit more about McManus’ details than just the colour of his pants though, he was that invasive on Sunday. He’d nearly have a fair idea of the workings of his insides, he spent so much time exploring his body.

Wherever McManus went, Hampsey wasn’t just following him, they were connected somehow, physically and emotionally. I’ve honestly never seen a player sprint with someone like McManus and literally do it stride for stride. The best player in Ireland was darting across the pitch but Hampsey’s toes were not leaving his heel. So, when McManus stretched his left leg, his marker’s left leg followed directly behind.

In that second period, no gap appeared between the two of them, not even for off-the-ball runs, not even for a second. Something was constantly connected because, for Hampsey, his brief was purely to understand that any breaking of that bond would unleash a world of pain on his county. So he did whatever he could to preserve the link and he had this unbelievable ability to match every single inch in perfect time with McManus and do it all whilst watching the play unfold too. At full flight, he was still engaged with McManus’ hip or McManus’ backside, whichever was closest to goals and, any time a ball came inevitably towards them, he was there. He was always there.

McManus still won possession, we’re talking about Conor McManus here. He still scored six from frees and one from play and he was still the out Monaghan were searching for every time but he won nothing without taking a few bruises to do so and he never got turned without Hampsey jumping all over him.

When Burns got hauled off at half time, it was Tiernan McCann who dropped into the space in front of the opposition focal point and you could see both him and Hampsey having a few words with McManus. Standing 30 feet away on the Hill, you could neither hear nor make out exactly what they were saying but it was clear the two Tyrone men were enjoying whatever it was they were discussing and it was clearer that it wasn’t anything outside of the topics of Conor McManus or Monaghan.

Sometimes you wonder about that carry on though. McManus is one of the most mild-mannered individuals in Gaelic football – he’s never reacted to abuse, he’s never done anything stupid and he doesn’t generally let anything put him off his game – so what’s the point in saying anything to him when he could just kill you with his right foot regardless? But twice in the second half he won the ball under severe pressure and he tried to swing over his shoulder for what would’ve been miraculous efforts, even by Conor McManus’ standards, and you wonder was he doing that to exact some sort of revenge on the men he’s having to endure this torture from for 73 minutes – but no more than 73 minutes. Hit the score of the championship and rub their faces in it, that’d be the best way to go but, if that was the motivation for swinging at those efforts, to get his own back on Hampsey and McCann and everyone else chiming in, then the abuse, on some level, works.

The same boy was still massive for his county, kicking huge scores with the pressure on, but, on the day, as his shadow, Hampsey was taking up more of the stage.

Hampsey was strong and quick, he was smart and disciplined and, wearing number nine on his back, he gave a masterclass of a full back performance.

He’s starred in midfield, he’s kept Michael Murphy under wraps and, in Croke Park, he wrestled with the beast to take Tyrone to a first All-Ireland final in a decade.

In an era where any sign of a defence getting on top is causing mass panic for the future of Gaelic football, one of the most beautiful performances of the 2018 championship was about nullification.

It had nothing to do with kick passing, with high scoring, it didn’t even have anything to do with the ball – it was just about total focus, commitment and precision. It was about spoiling the most effective forward in the game and, I’ll tell you, watching that display from behind the goals with the Hill marvelling at every single step the pair were taking, you’ll see fewer finer sights than the ability of Padraig Hampsey to execute one of the most fundamental tasks in the GAA: man-marking.

Hammering the hammer is a tired cliche in the game these days and it doesn’t even fit here anyway because Tyrone brought a wrecking ball to the hammer fight when they sent Padraig Hampsey in to do the job.