Who actually won the first replay to ever take place in a GAA Final? It depends who you ask.

It took place over 124 years ago in the 1894 Championship between Young Irelands of Dublin and Nil Desperandums of Cork. It was the capital’s third ever All-Ireland triumph, and you could argue that there should be an asterisk beside each of those first three. Especially that first ever Final replay.

But we’ll get to that.

Some things in the GAA never change, and the others stay the same. That’s what I learned by spending the best part of a week trawling through the history of the organisation in the 1890s. The 1894 All-Ireland Final replay was the nadir (or pinnacle, depending on your desire for controversy) of a tumultuous decade for the organisation.

On paper, the game had all the elements worthy of a momentous occasion; a crowd of around 8,000, in the home county of the GAA, attended by Archbishop Croke himself, the reigning All-Ireland champions putting their title on the line…

We just might not expect the clash to include a crowd that refused to keep off the pitch, a delayed throw-in because two other teams wanted to play a game first and refused to move, a few assaults thrown in for good measure and one side walking off the pitch with two minutes left to play.

We definitely don’t expect that both sides would claim to have won it.

But before we even get into that game, we have to understand the state the GAA found itself in at the time. Consider this a Chris Tarrent “but we don’t want to give you that!” moment: it’ll be worth hanging in there for a few extra 0s at the end of your cheque.

This story is worth telling.

Parnell, emigration and deaths on the field

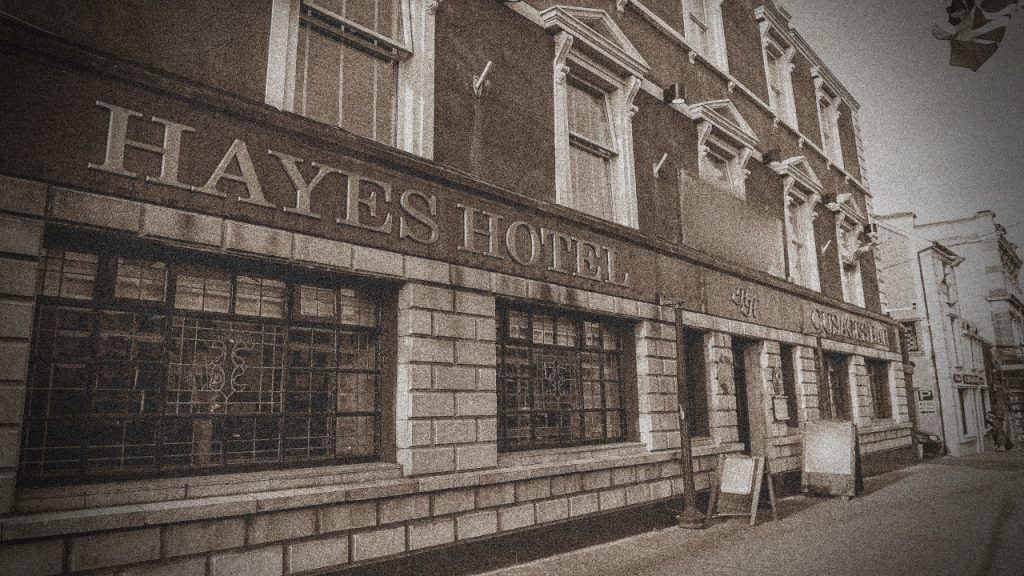

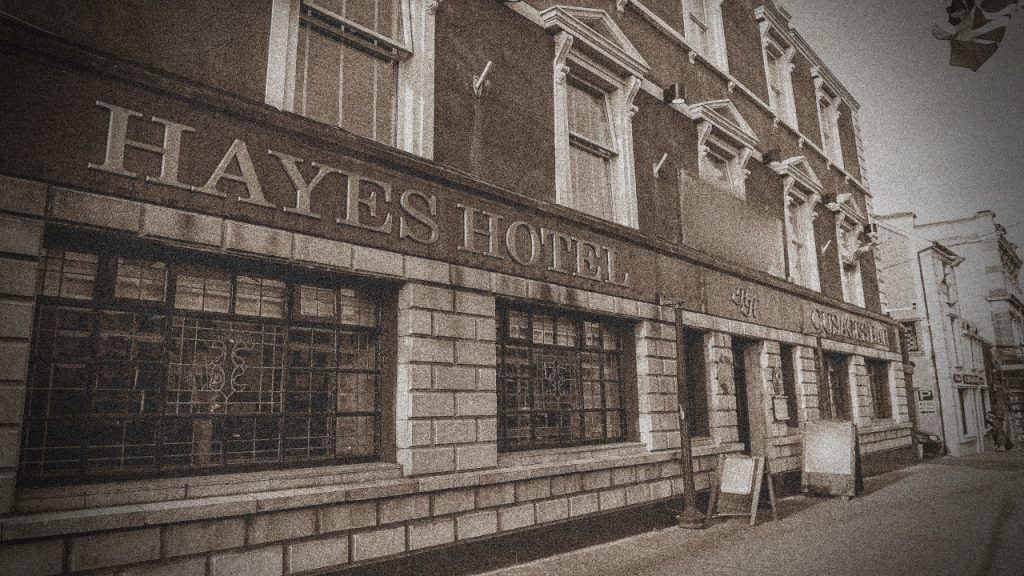

The GAA was born in Hayes' Hotel, Thurles on November 1st 1884, we've always known that much. One of the first secretaries Michael Cusack described its initial, rapid rise in popularity as being akin to the spread of a "prairie fire". However, the early success of the GAA quickly dwindled and the organisation almost toppled before it had even truly taken root in Ireland. That might sound dramatic, but it’s actually underplaying just how much the national game was in the doldrums in the 1890s.

This sorry state was due to a combination of economic recession, mass emigration, poor administration at county board level, unclear and easily misinterpreted playing rules, boring and over-defensive play from sides and not to mention regular interruptions from booze-fuelled fans. That’s before the fall of Charles Stewart Parnell split the organisation (and the country) in a manner similar to Roy Keane bailing out of Saipan.

Some things never change.

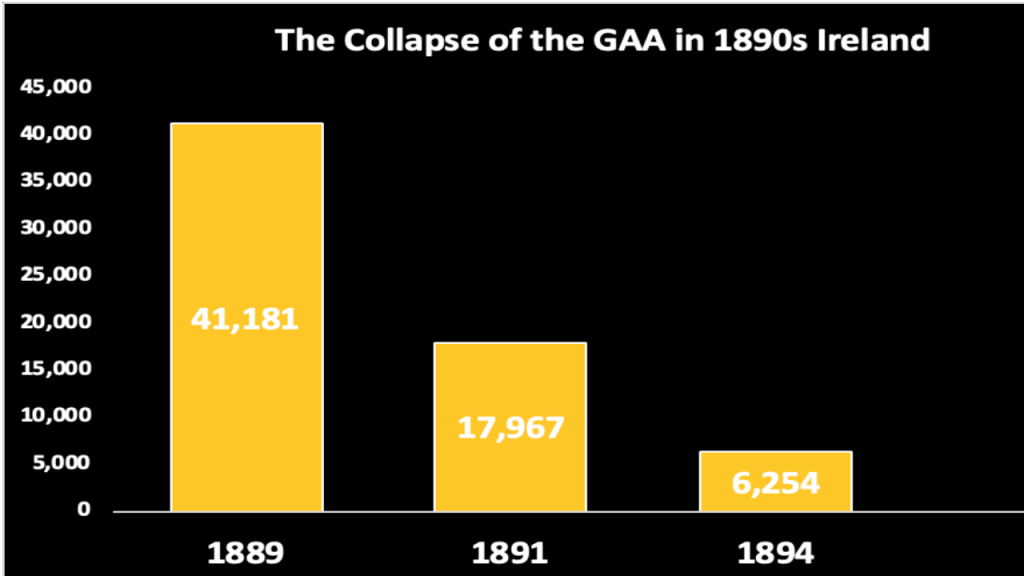

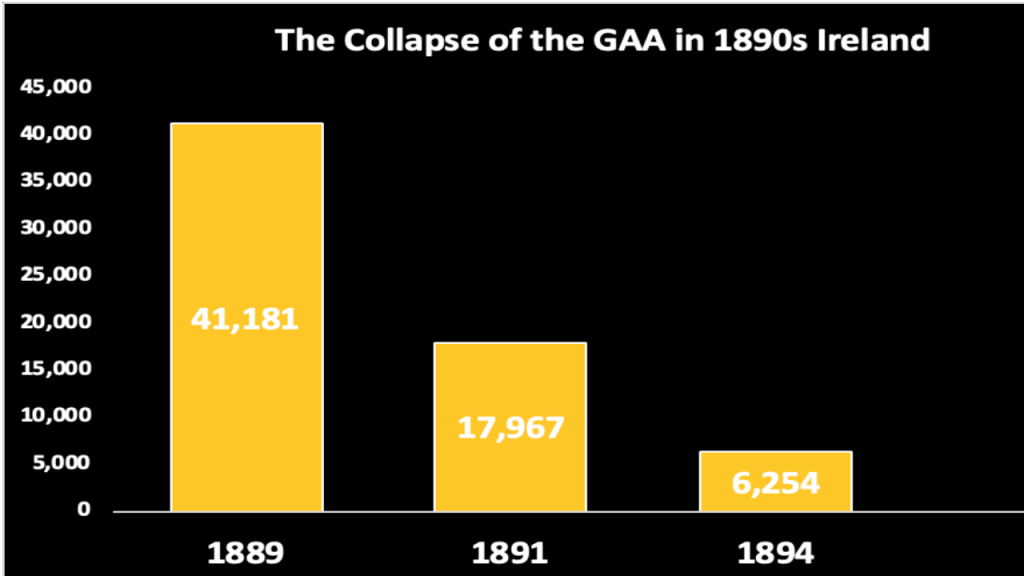

The drop in numbers involved in Gaelic Games, as a result of these factors, was nothing short of seismic. Between 1889 and 1894, the total numbers playing hurling and football in the country dropped from 41,000 to just over 6,000, a reduction of some 85%. That translated into an existence of just 118 clubs out of 777, and it's estimated that in at least 20 counties there was effectively no GAA in existence any more

From 'Quenching the Prairie Fire' by Dr Richard McElligott

A large drawback of football at the time was the sheer boredom of the game as a spectacle. For example, when Wexford and Cork managed 5 scores between them in the 1893 Final, the Freeman’s Journal declared that “rarely has a better exhibition of football been witnessed in the metropolis!”. Expectations for the game were through the ground at that point.

The GAA was quite simply on its knees, on the verge of extinction and police reports at the time noted this. Enter Richard Blake, who is credited by some, particularly Dr. Richard McElligott, with saving Gaelic Games in the country. Blake, a renowned match official and eventual Secretary of the GAA, brought in a series of rule overhauls in this decade that helped drag football from the abyss it was teetering over.

Over-carrying, 5-point goals and drink bans

Before 1892, games were decided by goals. Not the way your under 14 manager would sagely tell you, but literally. Simply, the team with the more goals at the end of the game won, points only came into consideration if no goals had been scored. Putting the ball over the bar was, ironically, pointless. In the 1891 Final, the Dublin side put their entire team on the goalline to prevent a goal from being scored. To remedy instances like this, the value of a goal was finally set at 5 points in 1892 and then reduced to 3 in 1896. This prevented teams from ‘blanketing’ their defences and prioritising merely stopping the other team from scoring.

Some things.

Each team fielded 21 players in the early years of the GAA, so 42-man matches were taking place on smaller pitches than we would expect today. This was reduced to 17 and then eventually to the 15 we know today during this time in order to prevent over-crowded pitches. The handpass rule was brought in and throwing was outlawed. Over-carrying was given its first definition, which in fact stands to this day, four steps. Ultimately, at the hand of Blake, the game of football was dragged into becoming a somewhat palatable spectacle as a result of these changes.

But the GAA was still reeling from low numbers.

One of the few things keeping players interested and involved was, to put it simply, drink. The sale of alcohol was restricted on Sundays at the time, similar to the old laws on Good Friday, and the easiest way around it was to be ‘travelling’ on the day/day before. As a result, fans or players who made a substantial journey (pretty common considering away fixtures, or even taking the scenic route to your local GAA club) could legally be served in their local public house. A cottage industry of alcohol was also established at games where spectators could have a drink before, during and after the action. Think "hats scarves and headbands", but pints. Lovely, illicit and sacrilegious pints. County Board meeting minutes at the time regularly deal with players being fined for drinking when not having travelled the required distance.

However, this was largely outweighed by pretty heavy deterrents. Players literally took their own lives into their hands when playing Gaelic Games at times. A combination of a lack of stringent rules and ineffective referees led to a number of recorded instances of players actually dying on the field in this decade. For example, in April 1897 Willie John O’Connell was struck in the head in a club hurling game in Cork City and died immediately. In August 1891, Benburb’s David Irons received a fatal kick to the stomach in a match against Clondalkin Round Towers. Perhaps the most shocking of these deaths came in September 1893, when a player from Doon was fatally stabbed in the heart by a crowd member during a match against Cappamore in Limerick, apparently due to a land dispute.

These crowd invasions were very common, and a number of games were called off as a result during this period. Matches were also routinely abandoned due to players walking off the pitch in protest at a refereeing decision, violence or teams simply not showing up to fulfil fixtures.

The violence, alcohol consumption and lack of clarity around the rules that were endemic in the GAA are the time are crucial in understanding the frankly bonkers fate of the first ever All-Ireland Football Final. It was not necessarily unusual for the time, but it certainly is when you consider how far Gaelic Games have come.

Still with me? Good.

The “usual crowd”, Timbuctoo and an accidental double-header

Although it is titled the 1894 Championship, the final actually took place on the 24

th March 1895. Fixture congestion: some things never change. The Dubs had home advantage for that first final in Clonturk Park, Drumcondra… The others stay the same.

Although the rules had recently been changed to allow counties to draw their teams from all over the region, the tradition of the club champions representing their counties in the All-Ireland continued strongly; 10 of the Cork side hailed from Nil Desperandums F.C. (Nils) and the entire 15 from Dublin were of the Young Irelands side that emerged from the Guinness brewery at James’ Gate. The first game ended in a 1-1 to 6 points draw, goals of course still counting for 5 points at the time.

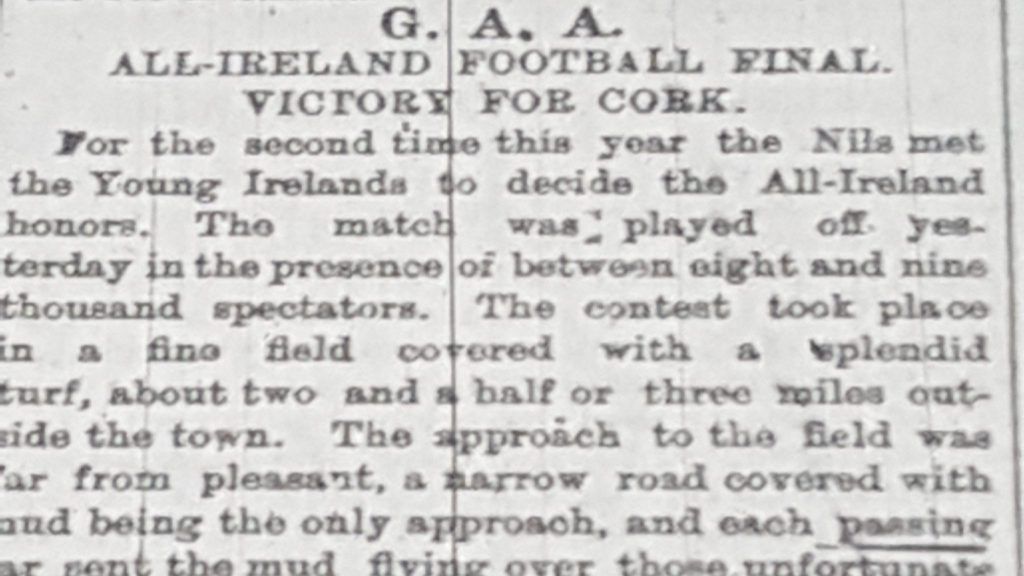

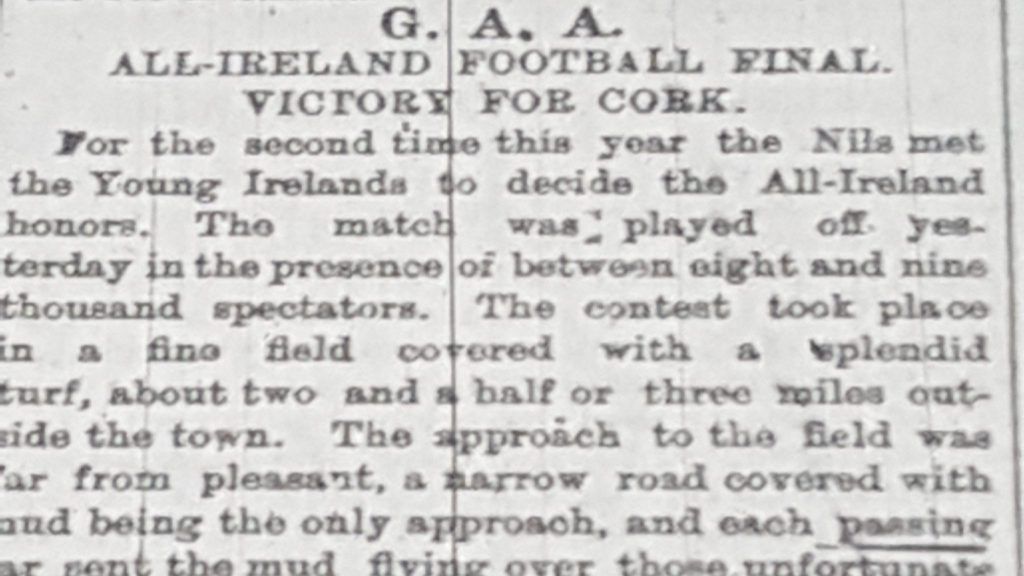

The replay was set for Thurles (we couldn’t get official confirmation, but we assume it was due to a college American Football game taking place in Clonturk Park). Special trains were commissioned to get fans to the game, and as a result a bumper crowd of, according to The Cork Examiner, between 8 and 9 thousand lined the pitch. Literally. At times, the ball was liable to strike spectators and still not be out of bounds, which caused frustration between the players and fans throughout the game. The final was also an impromptu double-header, after Tipperary clubs Inch and Arravale refused to make way for the Final as they had arrived there first, and played their county championship game while everyone else watched on, including the All-Ireland finalists.

According to newspaper and player reports, the game was finely poised with 2 minutes to go, Nils were leading by 1-2 to 5 points, when an incident occurred in a corner of the ground. It had been brewing for some time, with the Cork Examiner reporting that just minutes beforehand “A Young Irelander caught a Cork man by the neck and slung him to the ground” and the Independent described the Dublin side as playing “terribly severe” with a “wicked defence”.

The incident itself is best described by the Examiner’s special reporter;

“A Dublin player struck a member of the Cork team. A bystander, a Charleville man, shouted ‘foul’. A Young Irelander ran at the spectator and struck him, but got promptly a knock down blow in return. The usual crowd then ran in and the match was interrupted. A few minutes later the Dublin team left the field and objected to Cork getting the match on the ground that the field was badly kept, and that one of their players had been struck.” - Cork Examiner, 22nd April 1895

Whether or not the crowd member was from Cork or not turned out to be quite fiercely contested. The Independent specifically mentions that he was “not a Cork man”, and the Cork county board rep was quoted in a later meeting as saying “we are of the opinion that he was not a Cork man, and he must so be from Timbuctoo”. Regardless of that, the game was abandoned by Dublin for those two reasons; bad pitch, worse crowd.

So, the first All-Ireland Football Final replay was never actually completed. There was no winner. Both sides claimed it.

But we’re not finished yet. Buckle up.

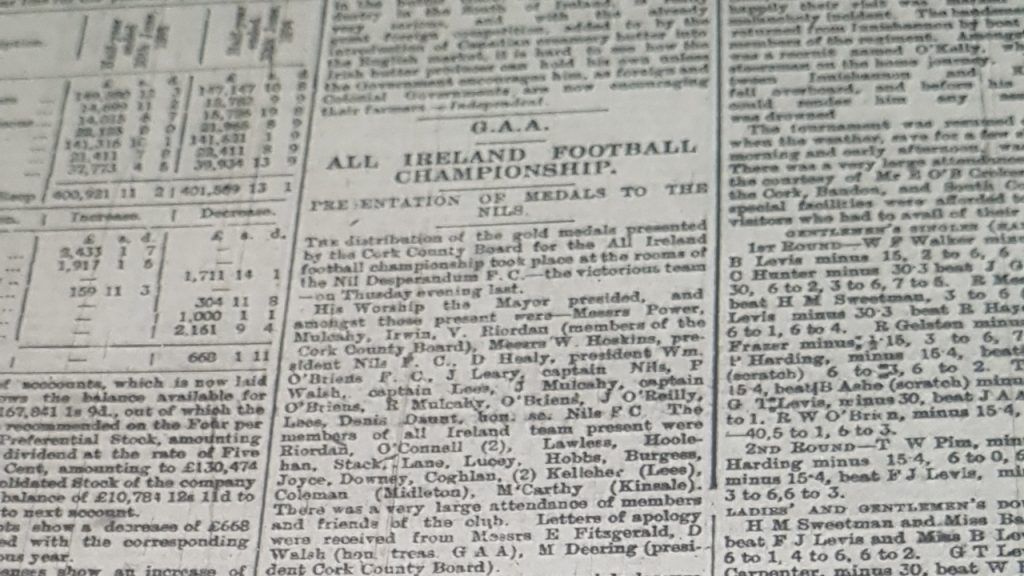

The Cork Examiner, 22nd April 1895. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Resignations, presentations and declarations

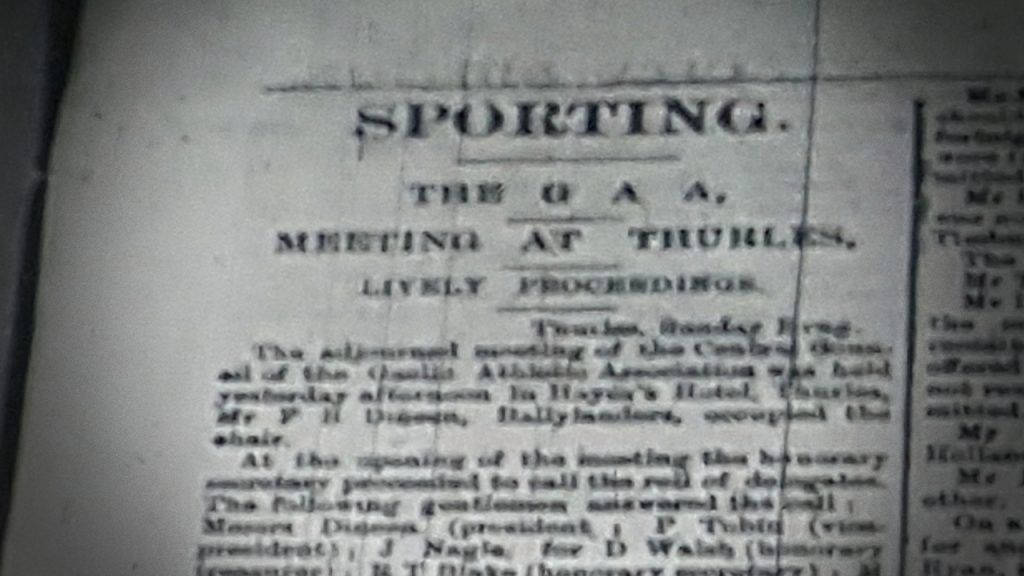

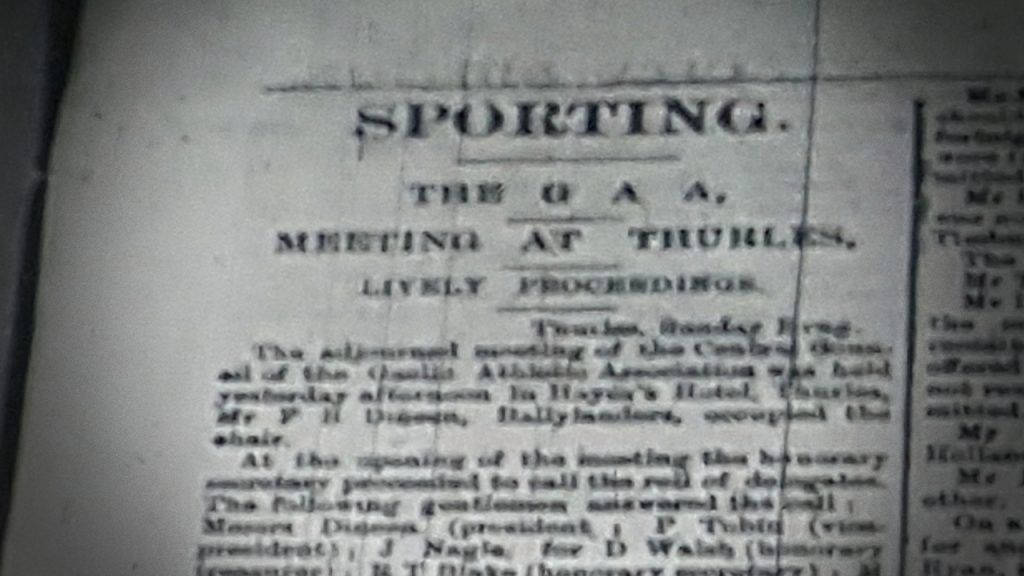

A special meeting of the GAA Central Council was convened for Hayes Hotel the following Sunday, 28

th April. The Examiner described the meeting in its headline as “lively proceedings”. The Chairman of the GAA said he had “never seen such a scene before”.

Blake’s refereeing was called into question for large periods, but the main focus of this meeting was to work out who would be crowned champions. Representatives from both clubs were present, along with the full 7-member Central Council of the GAA.

After particularly nasty words were exchanged between Blake and the Cork county board rep Michael Deering, three options were eventually put on the table; the match be replayed as a fresh encounter, the final two minutes be played with the scores as they were at the time of abandonment or the match would be played on for an hour more with the scores as they were. There was precedent with the final option, and that was decided as the best way forward. Deering refused to vote, the result was, ironically, a 3-3 draw and the Chairman gave a casting vote for the replay to occur in Limerick in three weeks’ time.

At this point, Deering stood up from his seat and gave the following speech;

“I am authorised by Cork to withdraw my membership on the Council, and, furthermore, I beg to inform this Council that the Cork people will give to this team that beat Young Irelands a set of medals as valuable as was ever presented. This is my resignation as member of the Council, and the treasurer of the Central Council will follow in my footsteps. Good evening, gentlemen.” - Cork Examiner, 29th April 1895

The Cork Examiner, 29th April 1895. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

He was true to his words.

The game was never replayed, despite being fixed for three weeks’ time. Newspaper reports on that weekend indicate that the new club championship season had begun, with the Examiner reporting on Cork club games taking place that weekend and the Independent similar with Louth county clashes. Dublin and Young Irelands were declared champions for the third time in four years. Cork were consigned to runners-up.

Officially.

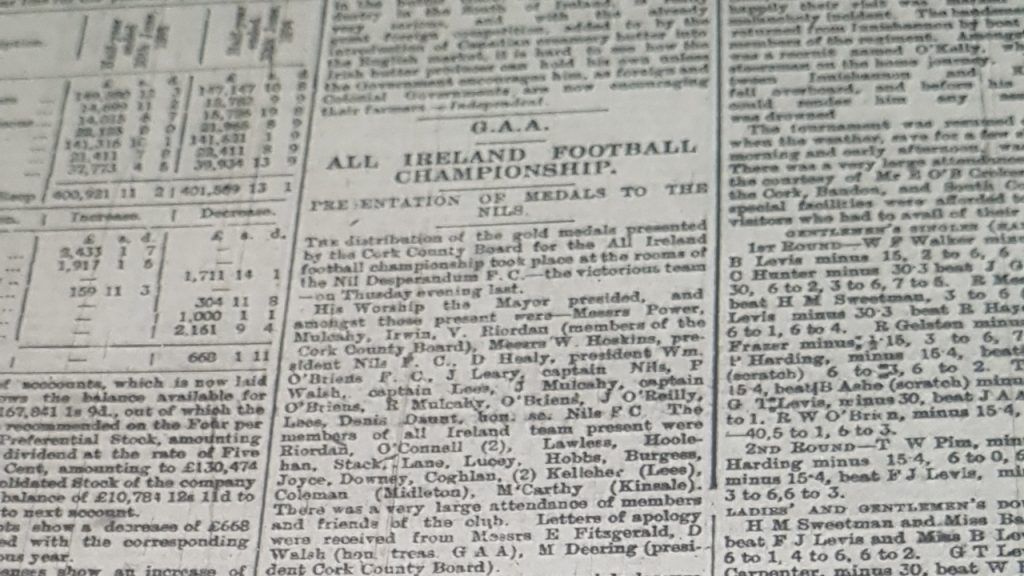

But, on the 30

th July, at the Nils clubhouse, the Cork team were presented with a set of winners medals. Although Deering himself was not present, the Mayor of Cork Patrick Meade obliged proceedings. Meade was also unequivocal in his declaration of Nils as champions, saying as he gave out the medals that the Cork side had

“defeated the famous Young Irelands. I am sorry some misunderstanding arose in connection with the last match as I believe that the Dublin Gaels as a body are not antagonistic to Cork. But…this trouble was created and fomented by a small section of Dublin who hold the opinion that the Young Irelands should never suffer defeat. I am positively certain that the Dublin Gaels…now hailed them (Nils) as the winners of the Football Championship for 1894.” - Cork Examiner, 3rd August 1895

The Cork county football and hurling champions then refused to take part in the 1895 All-Ireland Series in protest at the GAA’s decision to award the title. They would go on to organise their own tournaments until the schism was rectified. Deering would eventually go on to become President of the GAA, before his death in 1901.

The Cork Examiner, 3rd August 1895. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Young Irelands were champions, officially at least. While this story may seem scarcely believable at times, it certainly wasn’t the only contentious final that decade. In fact, Young Irelands other two titles in 1891 and 1892 ended in similar circumstances. In 1891, they were awarded the title over Cork (you can see why they lost the head in 1895) after one of the Rebels’ goals was chalked off

three hours after the final whistle. In 1892, against Kerry, the Dublin fans were the ones to blame for a dangerous atmosphere. It led to calls for a replay from the Kerry captain, published in a national newspaper, that Young Irelands initially agreed to, and then refused to play. Chalk another one up for the Dubs, I think.

In fact, if you take a look through a list of the hurling and football finals in that decade, you realise that very few of them are straightforward.

Some things never change, some things stay the same.

There you have it: the first ever All-Ireland Football Final replay, the 1890s in the GAA and question marks over Dublin’s first three All-Ireland titles. If Saturday’s final has even half the drama, we’re in for one hell of a battle.

With thanks to Dr Richard McElligott and his extensive research into the GAA during this period and to Katherine McSharry and the staff of the Reading Room at the National Library of Ireland.

However, this was largely outweighed by pretty heavy deterrents. Players literally took their own lives into their hands when playing Gaelic Games at times. A combination of a lack of stringent rules and ineffective referees led to a number of recorded instances of players actually dying on the field in this decade. For example, in April 1897 Willie John O’Connell was struck in the head in a club hurling game in Cork City and died immediately. In August 1891, Benburb’s David Irons received a fatal kick to the stomach in a match against Clondalkin Round Towers. Perhaps the most shocking of these deaths came in September 1893, when a player from Doon was fatally stabbed in the heart by a crowd member during a match against Cappamore in Limerick, apparently due to a land dispute.

These crowd invasions were very common, and a number of games were called off as a result during this period. Matches were also routinely abandoned due to players walking off the pitch in protest at a refereeing decision, violence or teams simply not showing up to fulfil fixtures.

The violence, alcohol consumption and lack of clarity around the rules that were endemic in the GAA are the time are crucial in understanding the frankly bonkers fate of the first ever All-Ireland Football Final. It was not necessarily unusual for the time, but it certainly is when you consider how far Gaelic Games have come.

Still with me? Good.

However, this was largely outweighed by pretty heavy deterrents. Players literally took their own lives into their hands when playing Gaelic Games at times. A combination of a lack of stringent rules and ineffective referees led to a number of recorded instances of players actually dying on the field in this decade. For example, in April 1897 Willie John O’Connell was struck in the head in a club hurling game in Cork City and died immediately. In August 1891, Benburb’s David Irons received a fatal kick to the stomach in a match against Clondalkin Round Towers. Perhaps the most shocking of these deaths came in September 1893, when a player from Doon was fatally stabbed in the heart by a crowd member during a match against Cappamore in Limerick, apparently due to a land dispute.

These crowd invasions were very common, and a number of games were called off as a result during this period. Matches were also routinely abandoned due to players walking off the pitch in protest at a refereeing decision, violence or teams simply not showing up to fulfil fixtures.

The violence, alcohol consumption and lack of clarity around the rules that were endemic in the GAA are the time are crucial in understanding the frankly bonkers fate of the first ever All-Ireland Football Final. It was not necessarily unusual for the time, but it certainly is when you consider how far Gaelic Games have come.

Still with me? Good.