Share

4th December 2017

06:53pm GMT

This tactic, allowing the opposition to play the short kick-out, as far as I could see, was actually stumbled upon by Cork in the 2009 semi-final against Tyrone when they surprised the nation by not alone beating them, but maintaining a five point half-time lead playing into a strong wind with fourteen men.

With fourteen men they were forced to concede the short kick-out to Tyrone. However, with five clever forwards they understood that the best thing to do, when faced two against one, is to back off the two opponents and blend into the re-enforced wall of defenders at midfield.

Cork were forced to apply a one up, 13 back system

This tactic, allowing the opposition to play the short kick-out, as far as I could see, was actually stumbled upon by Cork in the 2009 semi-final against Tyrone when they surprised the nation by not alone beating them, but maintaining a five point half-time lead playing into a strong wind with fourteen men.

With fourteen men they were forced to concede the short kick-out to Tyrone. However, with five clever forwards they understood that the best thing to do, when faced two against one, is to back off the two opponents and blend into the re-enforced wall of defenders at midfield.

Cork were forced to apply a one up, 13 back system

It worked out to consistently set Cork up with a bolt like 13 men behind ball, a position from which they completely stifled Tyrone who only managed five points to Cork’s five in the whole second half, a man up.

Inter-county sides cottoned on quickly that conceding short possession on the opposition’s kick-out wasn’t at all a bad thing, especially if it came with the added security of maintaining a sitting sweeper or two.

By 2011, Jimmy McGuinness had torn up the book on supposed football etiquette, cut out the nonsense, and didn’t even pretend to try to prevent the opposition from playing the ball to their defence.

He simply lined 13 and 14 up in their own half/two thirds of the field and let the opposition try to break them down.

He almost won an All-Ireland in his first year doing it. Again, statistics illustrated that, on average, Donegal were scoring significantly more on turnovers on the oppositions’ short kick-outs than they were conceding off them.

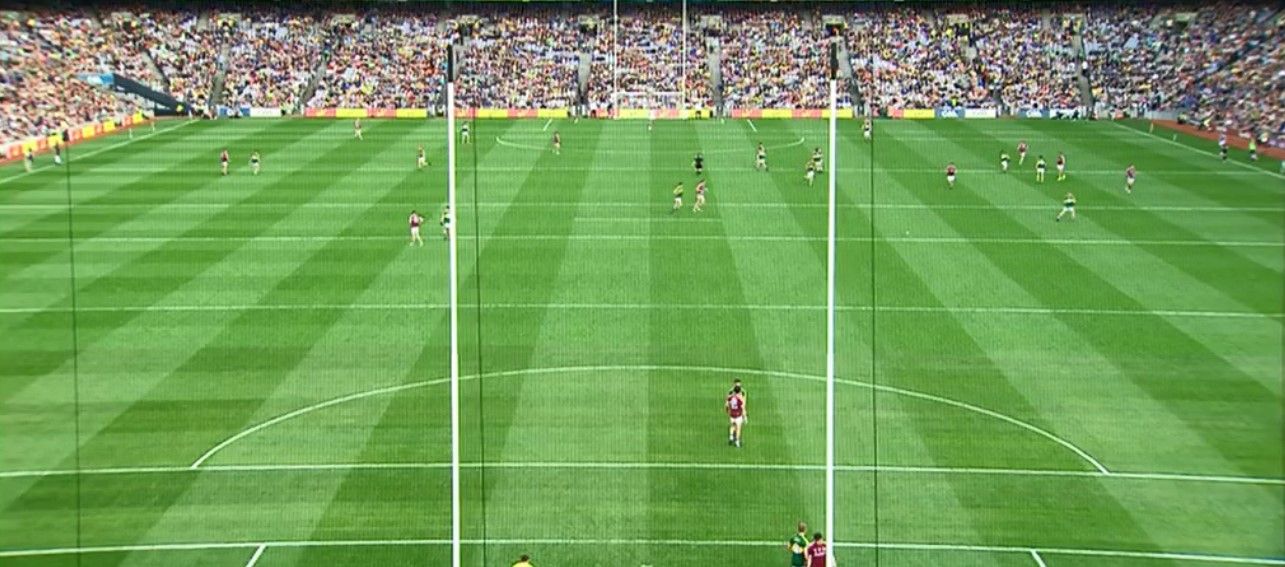

Donegal were happy to leave just one up and sit 14 at the back

It worked out to consistently set Cork up with a bolt like 13 men behind ball, a position from which they completely stifled Tyrone who only managed five points to Cork’s five in the whole second half, a man up.

Inter-county sides cottoned on quickly that conceding short possession on the opposition’s kick-out wasn’t at all a bad thing, especially if it came with the added security of maintaining a sitting sweeper or two.

By 2011, Jimmy McGuinness had torn up the book on supposed football etiquette, cut out the nonsense, and didn’t even pretend to try to prevent the opposition from playing the ball to their defence.

He simply lined 13 and 14 up in their own half/two thirds of the field and let the opposition try to break them down.

He almost won an All-Ireland in his first year doing it. Again, statistics illustrated that, on average, Donegal were scoring significantly more on turnovers on the oppositions’ short kick-outs than they were conceding off them.

Donegal were happy to leave just one up and sit 14 at the back

Then Jim Gavin came along and revolutionised the whole thing. He calculated that if you had athletically superior players, that could over-run the opposition, that there was indeed a value in playing short kicks to the full back line, but crucially, as long as you played them quickly.

Playing what even he would presumably consider, at this point, to have been somewhat naïve man-on-man tactics, they managed an All-Ireland in his first season with this ingenius new strategy.

All of a sudden, it became statistically important to bracket short kick-outs into two brackets - quick ones or slow ones. The figure I came to calculate as representing the statistically neutral point, in terms of who could be expected to get the next score, was 9.5 seconds after the ball had gone dead.

By the time Donegal came to town again in 2014, McGuinness realised that you could no longer let Dublin, now managed by Gavin, have the short kick-outs, at least not quickly.

The only way to prevent Dublin from dictating the pace of the game and running you into the ground was to prevent the short kick-out and dominate the long one. It’s a tactic which many a side have since aped, particularly at club level, but many have not fully understood.

The key point to this, however, was that it’s the athletically superior side who can afford to try to get the quick kick-outs off and attack at pace. The athletically inferior side can’t because they’ll run themselves into the ground. This creates a conundrum for the lesser athletic of two sides.

What to do? Try to get off the statistically hugely profitable quick kick-out and you’ll force the game to be played at a pace you can’t sustain against a fitter side.

Take your time on the kick-out while your opposition get theirs off quickly and you’re on a statistical loser – your opposition are playing statistically hugely profitable quick kick-outs while your side play statistically moderate/costly slow kick-outs.

For what it’s worth, even against top eight sides, Dublin’s “Expected Value” on quick kick-outs to the full back line runs at higher than 50 percent. Even subtracting scores conceded on the first turnover, it’s over 30 percent!

It’s a sticky wicket. What’s the answer? Try to go man-on-man on the opposition’s kick-out and choke off the quick, short one like McGuiness’ Donegal did to Dublin in 2014?

Of course, that requires attacking in numbers so you can be man-on-man when the opposition keeper gets the ball on the tee after six or seven kick seconds.

Alas, this brings its own problems which were at the root of Dublin’s aforementioned 2014 loss. If you go man-on-man on the kick-out you leave your side potentially exposed at the back as Dublin were against Donegal in 2014 (and against Tyrone in 2008 and Kerry in 2009 for that matter)

Dublin were man-on-man on the kick-out

Then Jim Gavin came along and revolutionised the whole thing. He calculated that if you had athletically superior players, that could over-run the opposition, that there was indeed a value in playing short kicks to the full back line, but crucially, as long as you played them quickly.

Playing what even he would presumably consider, at this point, to have been somewhat naïve man-on-man tactics, they managed an All-Ireland in his first season with this ingenius new strategy.

All of a sudden, it became statistically important to bracket short kick-outs into two brackets - quick ones or slow ones. The figure I came to calculate as representing the statistically neutral point, in terms of who could be expected to get the next score, was 9.5 seconds after the ball had gone dead.

By the time Donegal came to town again in 2014, McGuinness realised that you could no longer let Dublin, now managed by Gavin, have the short kick-outs, at least not quickly.

The only way to prevent Dublin from dictating the pace of the game and running you into the ground was to prevent the short kick-out and dominate the long one. It’s a tactic which many a side have since aped, particularly at club level, but many have not fully understood.

The key point to this, however, was that it’s the athletically superior side who can afford to try to get the quick kick-outs off and attack at pace. The athletically inferior side can’t because they’ll run themselves into the ground. This creates a conundrum for the lesser athletic of two sides.

What to do? Try to get off the statistically hugely profitable quick kick-out and you’ll force the game to be played at a pace you can’t sustain against a fitter side.

Take your time on the kick-out while your opposition get theirs off quickly and you’re on a statistical loser – your opposition are playing statistically hugely profitable quick kick-outs while your side play statistically moderate/costly slow kick-outs.

For what it’s worth, even against top eight sides, Dublin’s “Expected Value” on quick kick-outs to the full back line runs at higher than 50 percent. Even subtracting scores conceded on the first turnover, it’s over 30 percent!

It’s a sticky wicket. What’s the answer? Try to go man-on-man on the opposition’s kick-out and choke off the quick, short one like McGuiness’ Donegal did to Dublin in 2014?

Of course, that requires attacking in numbers so you can be man-on-man when the opposition keeper gets the ball on the tee after six or seven kick seconds.

Alas, this brings its own problems which were at the root of Dublin’s aforementioned 2014 loss. If you go man-on-man on the kick-out you leave your side potentially exposed at the back as Dublin were against Donegal in 2014 (and against Tyrone in 2008 and Kerry in 2009 for that matter)

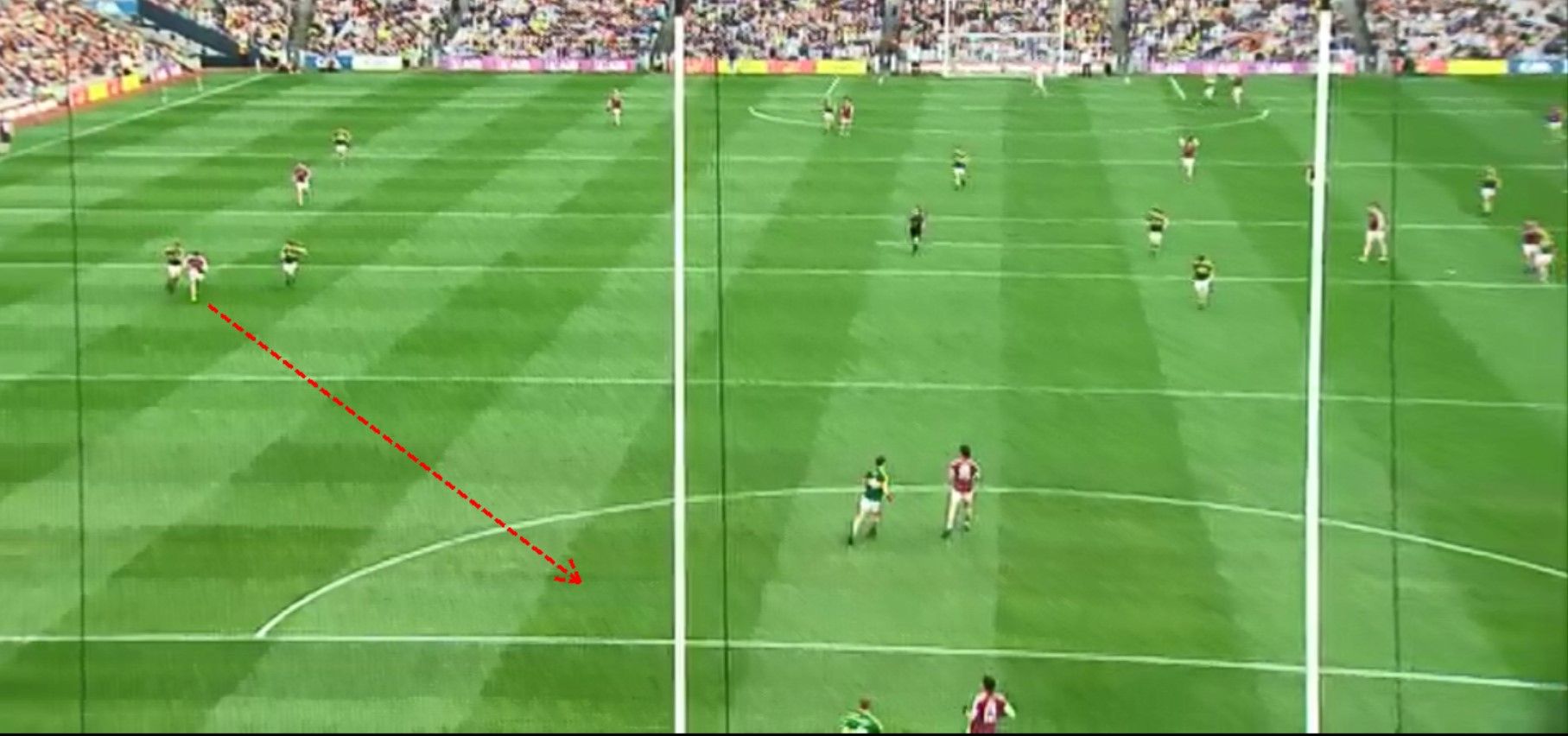

Dublin were man-on-man on the kick-out

But were instantly exposed when they lost the break

But were instantly exposed when they lost the break

Creating an easy Donegal overlap for a goal

Creating an easy Donegal overlap for a goal

The problem is that if you go man-on-man, the opposition can drag the majority of their side into your half and aim the kick-out over the top of all of them to a two-on-two or three-on-three attack.

In fact, broadly speaking, it’s quite tactically flawed to go man-on-man like this. Tyrone created a frighteningly easy one-on-one goal chance by applying this long kick-out over the top against both Donegal and Armagh in the championship this year.

Kerry conceded two frighteningly easy one-on-one goal chances against Galway by applying the same high pressing tactic. Galway went over the top, won the kick-outs and went one-on-one with the keeper twice.

Kerry go man-on-man with just two at the back

The problem is that if you go man-on-man, the opposition can drag the majority of their side into your half and aim the kick-out over the top of all of them to a two-on-two or three-on-three attack.

In fact, broadly speaking, it’s quite tactically flawed to go man-on-man like this. Tyrone created a frighteningly easy one-on-one goal chance by applying this long kick-out over the top against both Donegal and Armagh in the championship this year.

Kerry conceded two frighteningly easy one-on-one goal chances against Galway by applying the same high pressing tactic. Galway went over the top, won the kick-outs and went one-on-one with the keeper twice.

Kerry go man-on-man with just two at the back

And are completely exposed when they lose the kick-out

And are completely exposed when they lose the kick-out

Allowing Galway the simplest one-on-one shot

Allowing Galway the simplest one-on-one shot

With many sides now potentially ready to spring the same kick-out trap, it’s simply naïve to unconditionally go man-on-man on the opposition’s kick-outs.

So after eight years of tactical evolution we’re now back to square one where the only statistically and tactically sound principal is this – if the opposition drag large numbers into their own half on the kick-out, allow them the extra man and try to “split” them, knowing that it’s not the end of the world if they get the short one off.

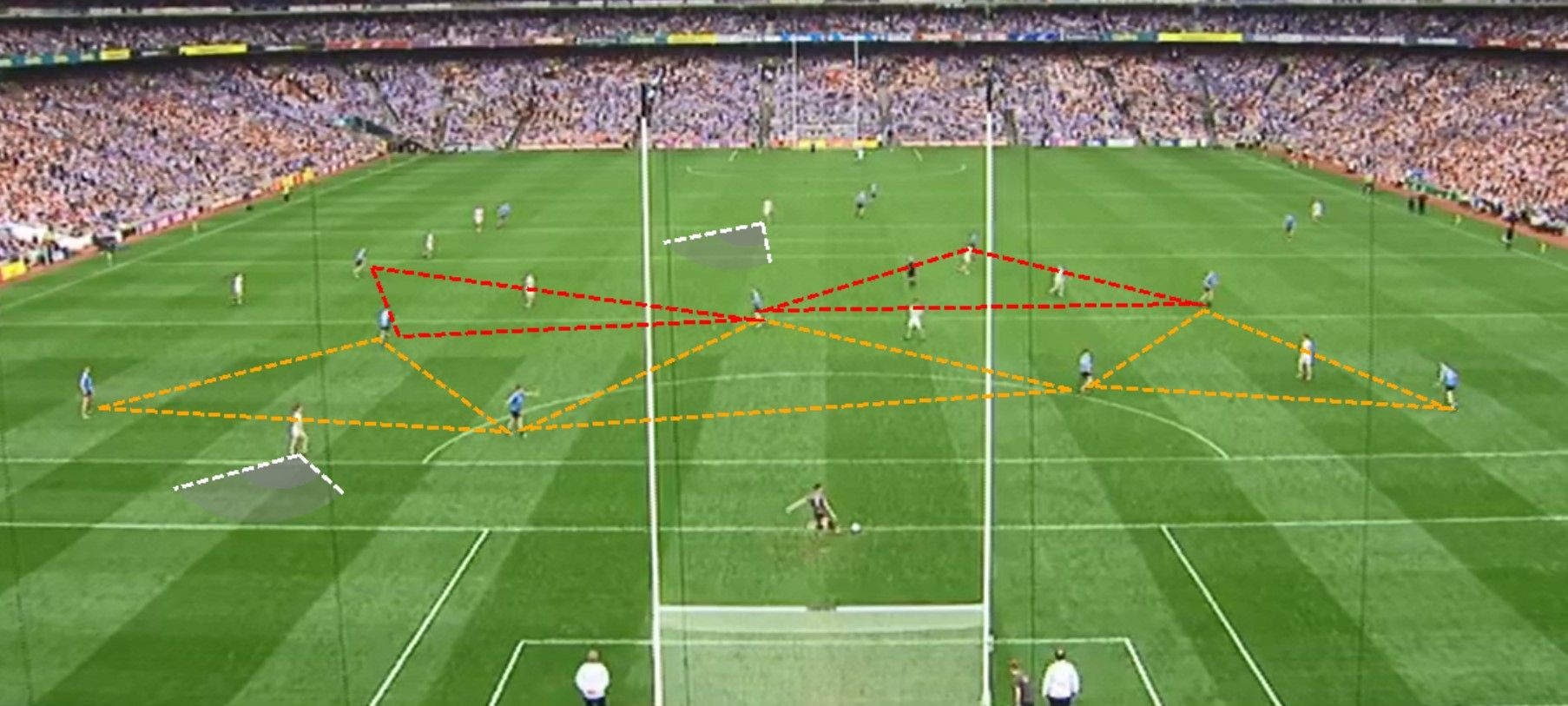

Dublin have developed a superb strategy on this which makes the short option risky for the opposition but keeps a spare man at the back to mind the house. They crucified Monaghan and Tyrone with it.

Dublin cover triangular zones extremely effectively

With many sides now potentially ready to spring the same kick-out trap, it’s simply naïve to unconditionally go man-on-man on the opposition’s kick-outs.

So after eight years of tactical evolution we’re now back to square one where the only statistically and tactically sound principal is this – if the opposition drag large numbers into their own half on the kick-out, allow them the extra man and try to “split” them, knowing that it’s not the end of the world if they get the short one off.

Dublin have developed a superb strategy on this which makes the short option risky for the opposition but keeps a spare man at the back to mind the house. They crucified Monaghan and Tyrone with it.

Dublin cover triangular zones extremely effectively

Broadly speaking, it represents a less risky “expected value” on score concession off the kick-out.

If your defensive unit is solid, statistics still read that you’re more likely to score on the counter-attack than they are from the initial possession – if they don’t get the kick off in under 9.5 seconds!

The key is to split them efficiently enough to make the quick, short kick-out a risky proposition.

Broadly speaking, it represents a less risky “expected value” on score concession off the kick-out.

If your defensive unit is solid, statistics still read that you’re more likely to score on the counter-attack than they are from the initial possession – if they don’t get the kick off in under 9.5 seconds!

The key is to split them efficiently enough to make the quick, short kick-out a risky proposition.Explore more on these topics: