As tactics have evolved rapidly and radically in Gaelic football over the last number of years, the role of the goalkeeper has become all the more important.

We’ve evolved from the long and hard kick-out to the goalkeeper becoming something more akin to the quarter back in American football.

As different plays and patterns evolve off the kick-out there is huge scope for cutting edge analysis to gain percentages by categorising different types of kicks and working out which patterns represent the most likely positive outcome for a side, based on previous records.

There’s a lot of nuance and the differences in “Expected Value” of outcomes between different sides can swing radically on different types of kick-outs.

For example, based on previous patterns and figures of their own kick-outs, as a statistician, you might tell one side that they should always go short to full back line if they can, but failing that, they should go long to midfield.

Another side’s figures, however, could suggest that they’d be better off with a policy of going short quickly to the full back line if they can, but if they can’t, still to go to the full back line if they have the opportunity. Going long in any circumstances might represent a higher risk of conceding scores than gaining them.

With all of this, however, there is one statistical elephant in the corner – a type of kick-out which is a bad option virtually across the board. That is the kick-out to the half back line that’s not hit inside 11.5 seconds!

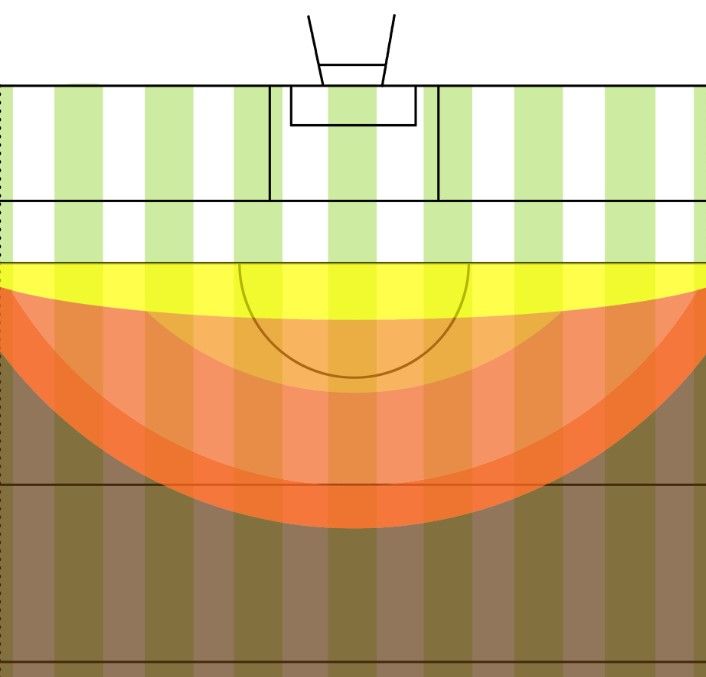

The central orange zone is always categorised as the half back line, the lighter orange is categorised as half back line (not full back line) if it takes out three opponents or more, and the darker orange is categorised as half back line (not midfield) if it doesn’t take out five opponents or more.

With over two thousand kick-outs of analysis from over forty different club and county teams, I’ve found just one side to have made a profit from this kind of kick-out, and that has only been as of their 2017 form – Stephen Cluxton and Dublin.

The problems with kicking to the half back line are multiple, but first let’s have a brief look at kick-outs to the full back line to give a context.

The simplest and most effective kick-out strategy across the board has been the quick kick-out to the full back line. Typically, the keeper can hit his target easily and his team can catch the opposition off guard.

Slow kick-outs to the full back line are far less profitable. If the kick isn’t hit within 9.5 seconds of the ball going dead, you can expect to have to break down thirteen, fourteen, or fifteen of the opposition. It’s not an easy thing to do.

My figures have shown that only a handful of club teams actually score more off their initial possession than they concede off the first turnover in this situation.

Alluding to pure footballing quality, Kerry were always an outlier at inter-county level in this regard, but as management teams and attacking structures have become more savvy, most of the top county sides have begun to make a profit off the short kick-out to the full back line, even if it’s not hit inside the magic 9.5 seconds.

Starting to see the problem with kick-outs hit to the half back line quickly (11.5 seconds is the magic number when it comes to kicks to the half back line).

At least when you go short, but not quickly, to the full back line, the keeper is typically hitting an easy target, close to him. Also, if the receiver is under any pressure when he grasps the ball, there’s the easy “out” of a hand-pass back to the keeper, where possession maintenance should be straight forward.

Even at that, most sides concede more off the first turnover than they do off the initial possession.

Going to the half back line, however, unless it’s done quickly, there are two added negative dynamics.

Firstly, the target is far more difficult to hit.

It’s classic hunter-gatherer psychology from the keeper. They can see the player running forty odd yards away and think “I can hit him”. They know they can hit him. But I beg the question – with what percentage of accuracy can you expect to hit him?

Most keepers, if asked, would probably tell you that they have over a ninety percent chance of hitting their target. Unless they’re top class strikers of the ball, they’re over-estimating their ability.

Typically, over thirty percent of these efforts go over the side-line, are won by the opposition or else the opposition force a free or turnover within two seconds of the receiver catching the ball.

- So, over thirty percent of the time this kick-out is attempted, the opposition receive the ball in your half back line.

- The majority of the time, they’re bearing straight down on goal.

Is it really worth the risk?

Even if your side gain possession, by the time the receiver has typically run towards the ball, the opposition will have twelve or thirteen behind the ball anyway. It’s rarely the kick-out to the half back line even takes out four opponents.

So, having taken what typically runs at about a thirty percent chance of the keeper not reaching his target successfully, even when you win the ball, your side will still find themselves in a position similar to the short kick-out to the full back line. That is that unless you’re one of the top sides in the country, you still run a higher chance of conceding a score on the turnover than you do from your possession.

And you’ve already run a thirty percent risk of the kick-out being won by the other side!

Of course, even within the confines of the kick-out to the half back line, there are various different dynamics with different types of situations. If you have a top-class kicker with a good brain in goal, as a coach, there might be a value in allowing an element of initiative to be used based on the situation.

It is worth noting, however, that until Dublin’s figures this year, no side I’d analysed for three or more championship games against top ten teams (in their championship) had ever made a profit off these – even Dublin in 2016!

With Stephen Cluxton in goal, Dublin became the first to break the mould this year.

Unless, however, you have a Stephen Cluxton in goal, typically, keepers should be under instruction that if they haven’t got the kick-out off inside 11.5 seconds, aiming for the half back line should simply be banned!

Stephen O’Meara supported the Galway hurling performance analysis team in 2017 and is the creator of Gaaprostats, statistical and video analysis software designed specifically for Gaelic football and hurling.