Share

21st August 2019

11:24am BST

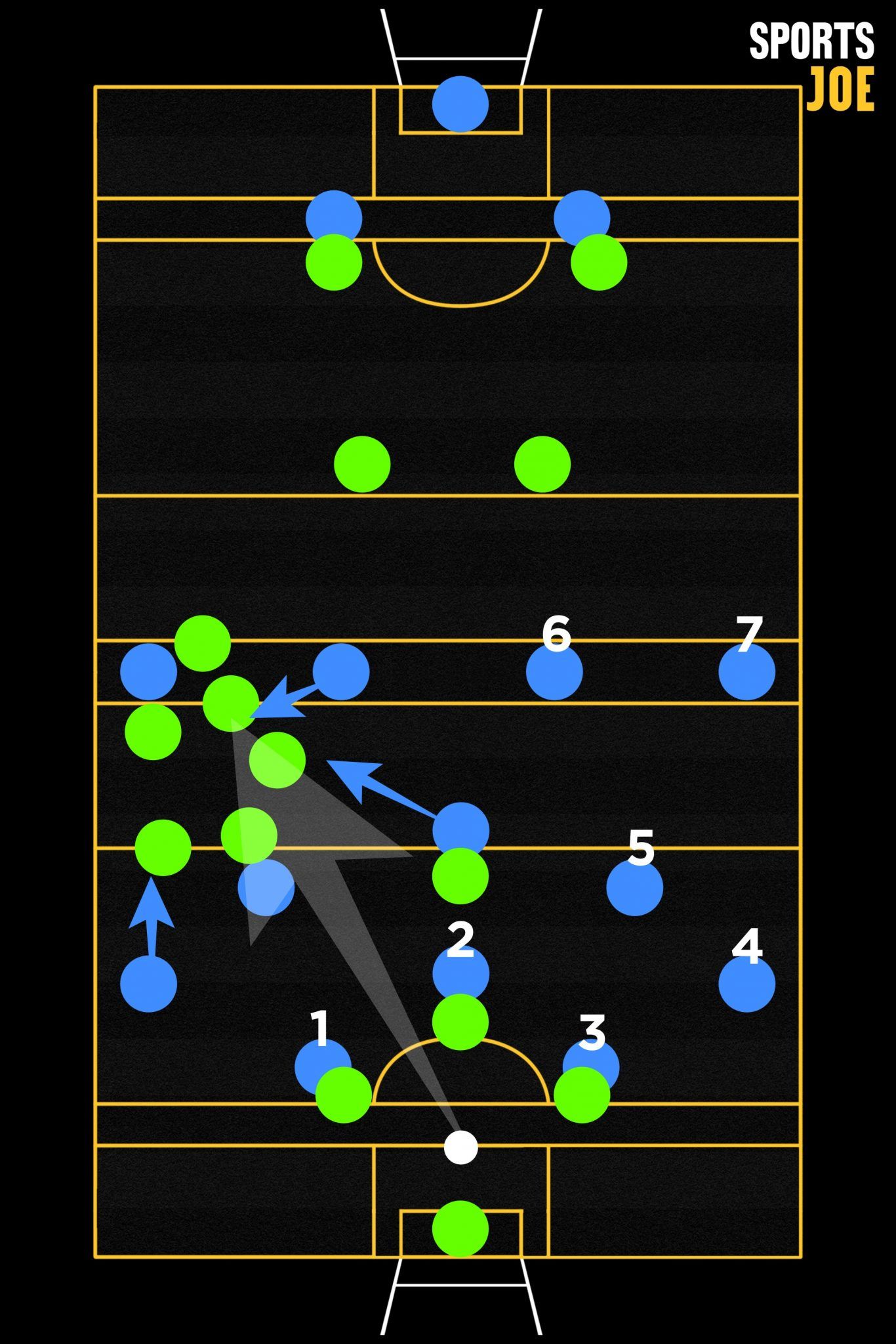

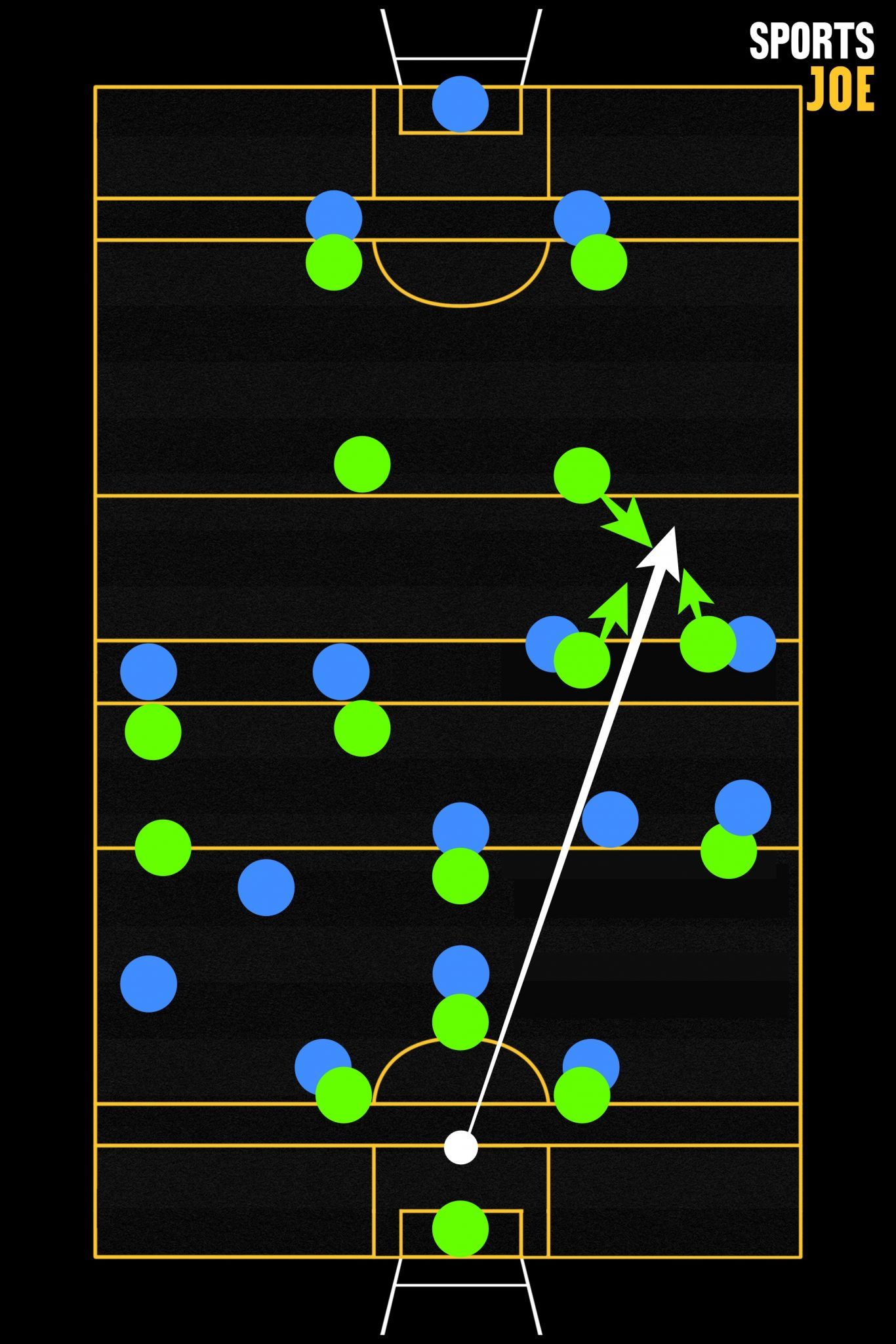

Wherever Hennelly would try to exploit, any little gap he might've thought that he saw, or whatever player he fancied to contest, Dublin had the shape, the personnel and the sheer volume of numbers that meant they could form triangles in every single pocket of the pitch.

No matter where the ball was going to be kicked, a Mayo man was getting smothered.

So Hennelly tried the wing and he tried to hit the patches but it was never on - even if it looked like it was.

Wherever Hennelly would try to exploit, any little gap he might've thought that he saw, or whatever player he fancied to contest, Dublin had the shape, the personnel and the sheer volume of numbers that meant they could form triangles in every single pocket of the pitch.

No matter where the ball was going to be kicked, a Mayo man was getting smothered.

So Hennelly tried the wing and he tried to hit the patches but it was never on - even if it looked like it was.

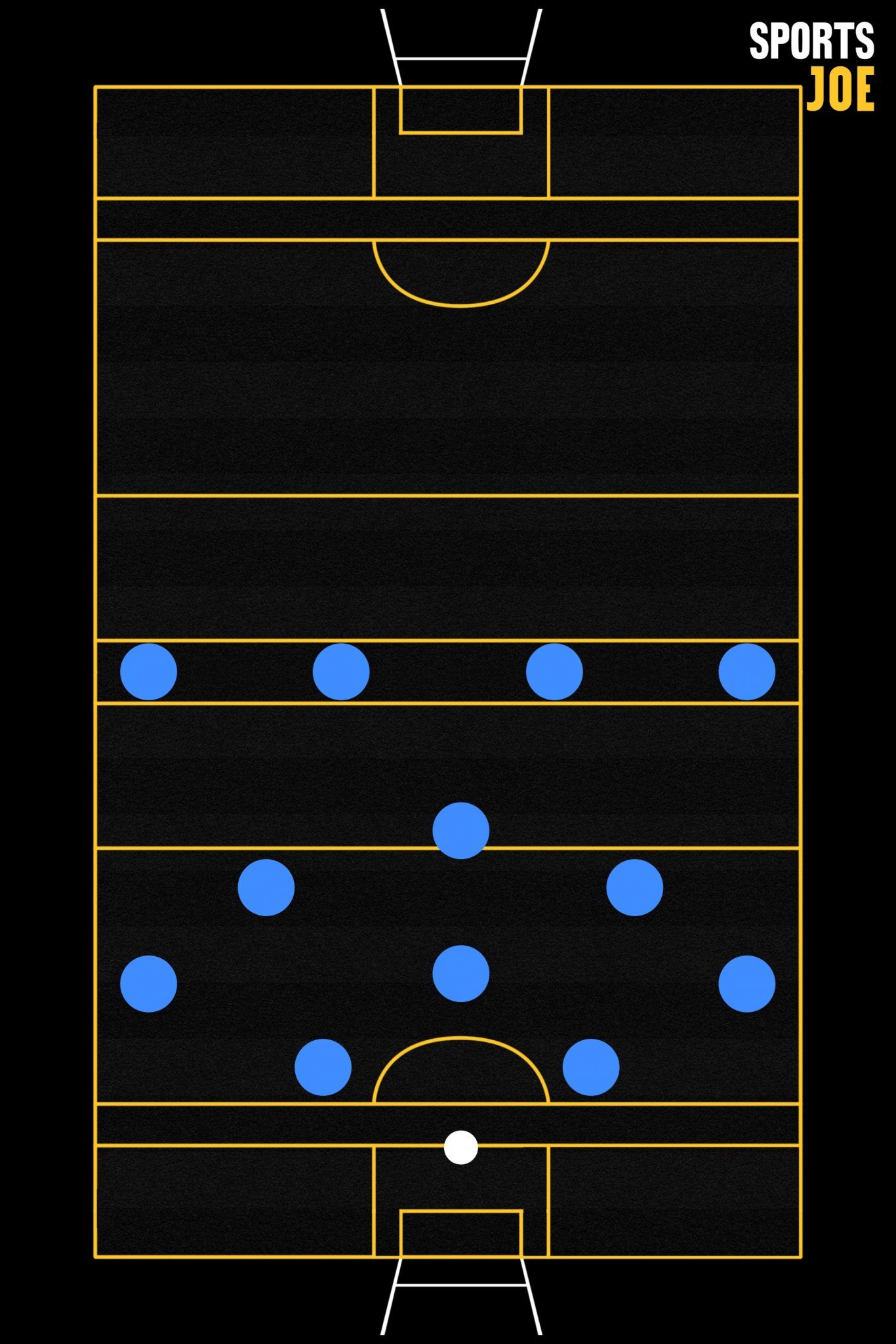

Occupying the Mayo half with 12 players meant that Dublin could close down every inch between the half way line and the 21'.

So, even when Mayo won the ball from their own kickout - like they did four times in that 12-minute spell - Dublin could close them down and put enough pressure on to win it back - like they did twice with those four successful Hennelly kicks.

And if a team goes short, then Dublin licks their lips because the press comes into its full effect. They can form the triangles they want to around players, they can hit them, they can chase them and they basically laugh at any team thinking they can work the ball out from their 21-metre line for 76 minutes against that press and against those athletes.

Occupying the Mayo half with 12 players meant that Dublin could close down every inch between the half way line and the 21'.

So, even when Mayo won the ball from their own kickout - like they did four times in that 12-minute spell - Dublin could close them down and put enough pressure on to win it back - like they did twice with those four successful Hennelly kicks.

And if a team goes short, then Dublin licks their lips because the press comes into its full effect. They can form the triangles they want to around players, they can hit them, they can chase them and they basically laugh at any team thinking they can work the ball out from their 21-metre line for 76 minutes against that press and against those athletes.

Traps

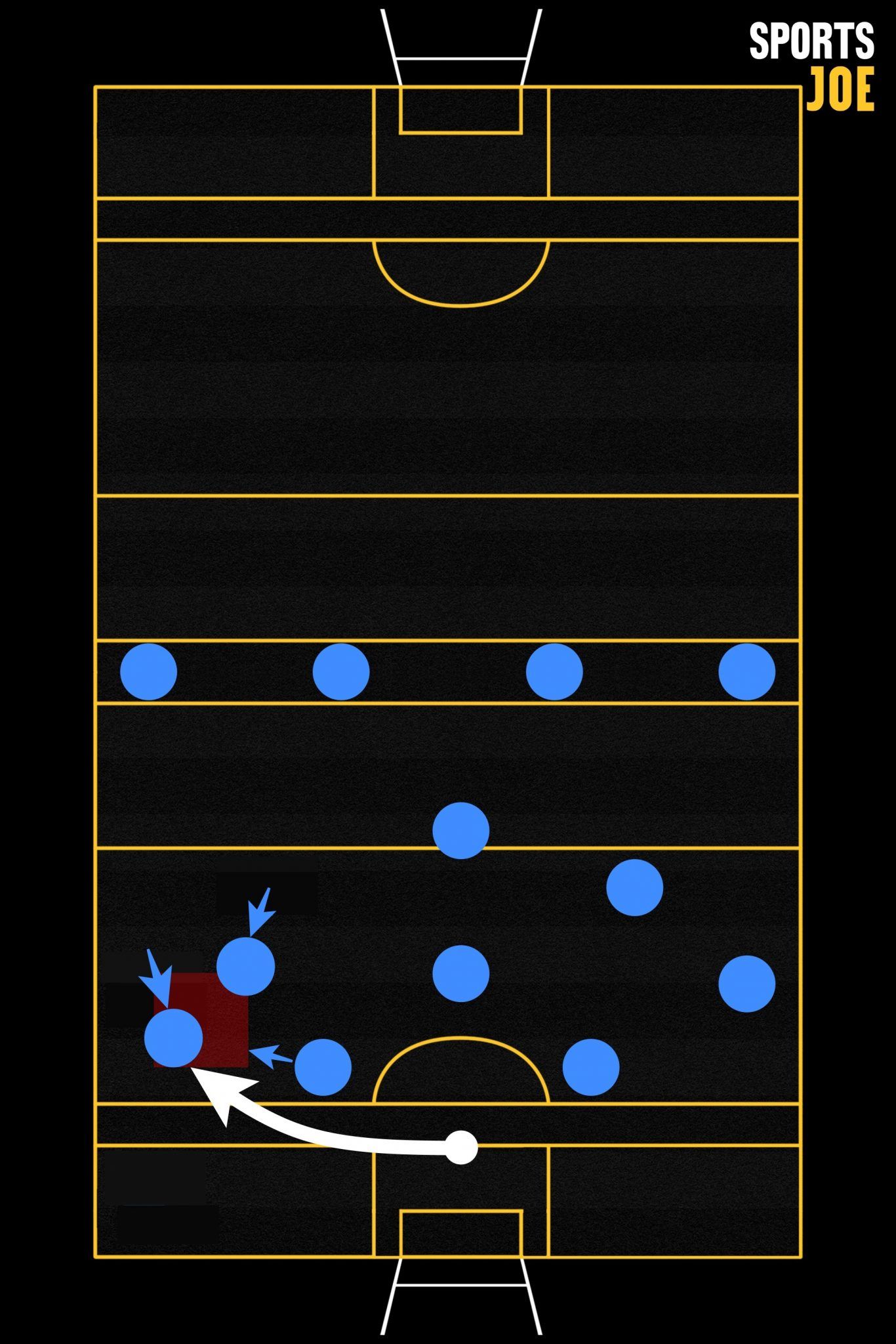

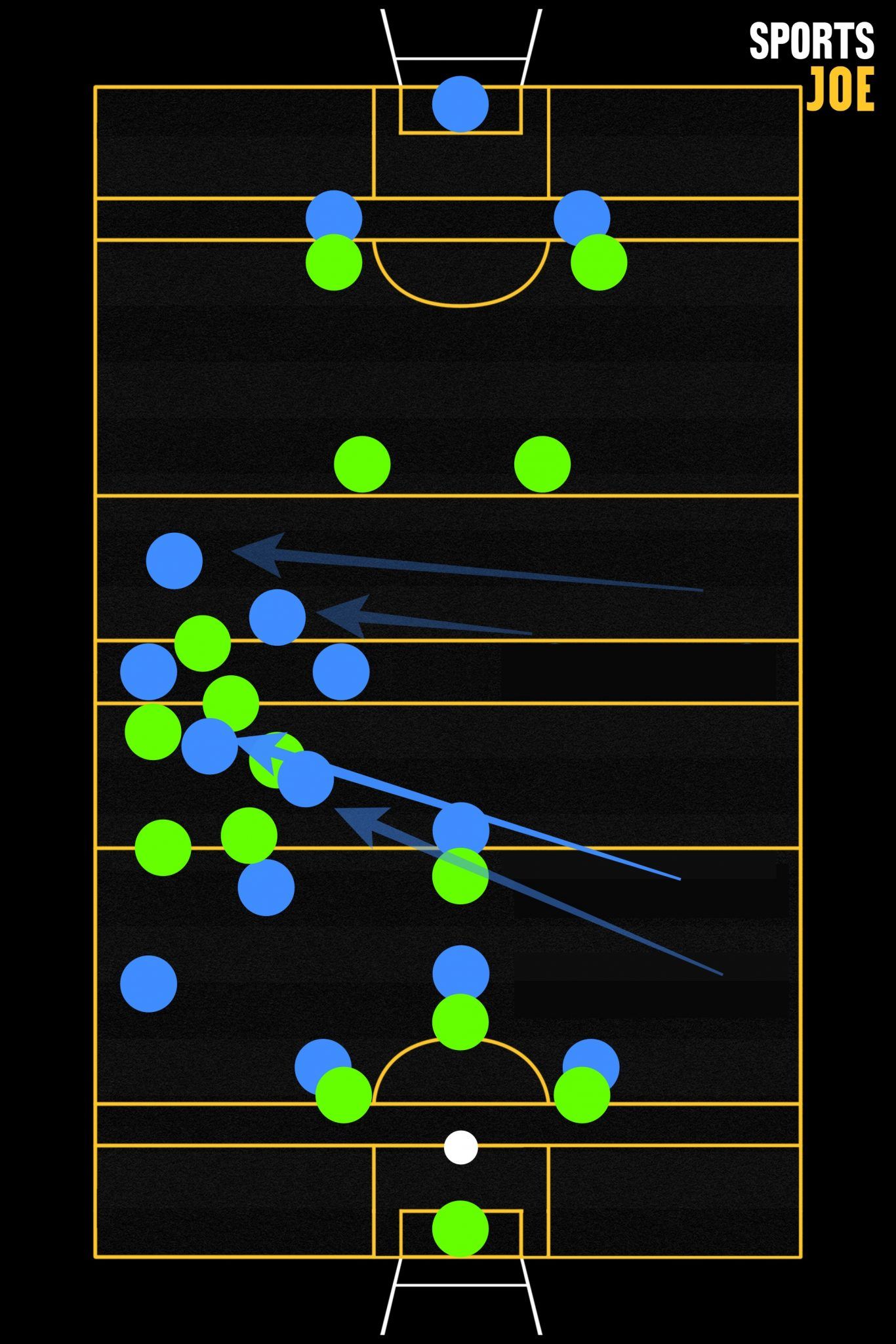

What Dublin also do very cleverly is the angle of their pressure.

It's not just numbers or conditioning that makes it so hard to get out of defence against them, it's the traps that they set.

Dublin want you to go short so they can bully you. They want you to hit those spaces you think the wide men can't see so they can surround you. But then, most interestingly, they want you to take off down the wing - into the space.

Watch for it. A team wins a break or gets their own kickout away short and they're basically sheep-dogged into the flanks. The killer here is that there's space there initially so a player goes for it with good, positive intentions and that's when he's trapped.

For a start, he's never going to lose the man he's taking on - Dublin are too fit and too disciplined to beat in a foot race so he's running under pressure from the off. But the angle of that pressure is fascinating. Rarely will that same Dublin player commit so much to a challenge that he'll lose his position. You see, the most important thing is to not let that man in possession to get inside at this stage because that's where the play can be opened up, that's where there are more options and that's where there's a bigger space that Dublin can't trap you so easily.

So the Dublin player will shadow him accordingly and continue to show him the wing. He's on one side, the sideline is on the other and, eventually, the ball-runner is going to meet another blue jersey head on - a bigger one.

He can't get inside because of the angle of the initial pressure. He's been shown nothing but the wing so his only other choice is to finally turn back down that same straight line he's been sprinting up and bang... another Dub is in on the plan and the man with the ball is surrounded and isolated with three men who are using the sideline as a fourth defender.

Traps

What Dublin also do very cleverly is the angle of their pressure.

It's not just numbers or conditioning that makes it so hard to get out of defence against them, it's the traps that they set.

Dublin want you to go short so they can bully you. They want you to hit those spaces you think the wide men can't see so they can surround you. But then, most interestingly, they want you to take off down the wing - into the space.

Watch for it. A team wins a break or gets their own kickout away short and they're basically sheep-dogged into the flanks. The killer here is that there's space there initially so a player goes for it with good, positive intentions and that's when he's trapped.

For a start, he's never going to lose the man he's taking on - Dublin are too fit and too disciplined to beat in a foot race so he's running under pressure from the off. But the angle of that pressure is fascinating. Rarely will that same Dublin player commit so much to a challenge that he'll lose his position. You see, the most important thing is to not let that man in possession to get inside at this stage because that's where the play can be opened up, that's where there are more options and that's where there's a bigger space that Dublin can't trap you so easily.

So the Dublin player will shadow him accordingly and continue to show him the wing. He's on one side, the sideline is on the other and, eventually, the ball-runner is going to meet another blue jersey head on - a bigger one.

He can't get inside because of the angle of the initial pressure. He's been shown nothing but the wing so his only other choice is to finally turn back down that same straight line he's been sprinting up and bang... another Dub is in on the plan and the man with the ball is surrounded and isolated with three men who are using the sideline as a fourth defender.

All a 'keeper is left with in that case - like Rob Hennelly was - is to go long.

Go long and high, get the ball out, give the defenders a rest and give your midfielders the opportunity to relieve the pressure.

All a 'keeper is left with in that case - like Rob Hennelly was - is to go long.

Go long and high, get the ball out, give the defenders a rest and give your midfielders the opportunity to relieve the pressure.

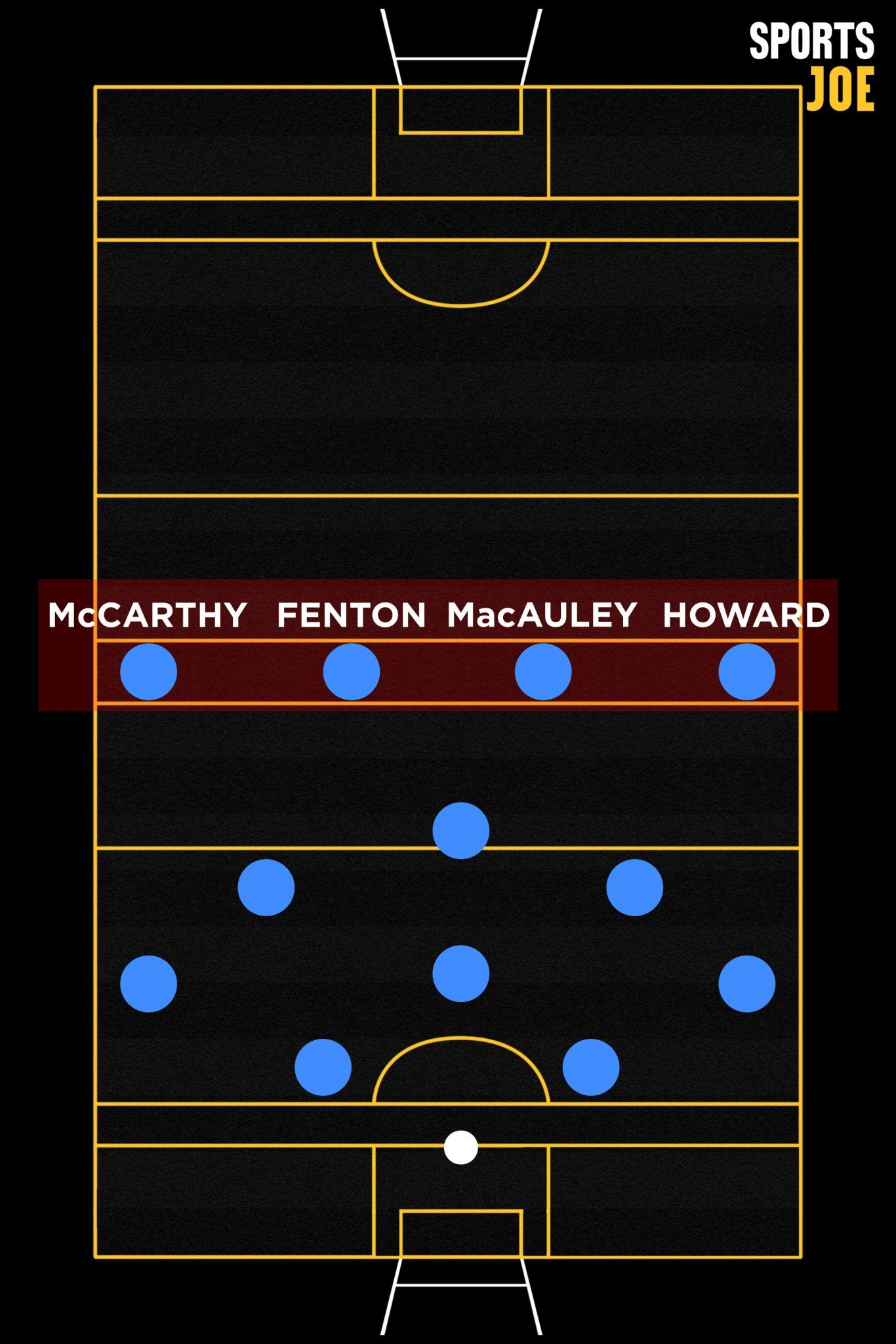

Go long and that's when you hit what should heretoforth be known as The Wall.

A line worthy of it's capital letters. An imposing line across the middle made up of James McCarthy, Brian Fenton, Michael Daragh MacAuley and Brian Howard.

Go long and that's when you hit what should heretoforth be known as The Wall.

A line worthy of it's capital letters. An imposing line across the middle made up of James McCarthy, Brian Fenton, Michael Daragh MacAuley and Brian Howard.

If you choose to go long against Dublin - which makes sense because they'll trap you if you go short, you're choosing to go long against the most competitive, most aggressive, most aerially dominant foursome the sport has witnessed.

Rob Hennelly tried three things against Dublin - he genuinely didn't just give up on it - and plenty of other teams have tried the same but the reality is that their set-up made every one of those attempts redundant.

If you choose to go long against Dublin - which makes sense because they'll trap you if you go short, you're choosing to go long against the most competitive, most aggressive, most aerially dominant foursome the sport has witnessed.

Rob Hennelly tried three things against Dublin - he genuinely didn't just give up on it - and plenty of other teams have tried the same but the reality is that their set-up made every one of those attempts redundant.

Kerry could give them a different problem.

With Paul Geaney, David Clifford, Killian Spillane, Sean O'Shea and Stephen O'Brien, Keane should always have at least three - if not four - players left in attack for their own kickouts. And they can win the ball without those players coming back for their own kickout - a mistake that so many make when they all get sucked in to helping out.

Kerry could give them a different problem.

With Paul Geaney, David Clifford, Killian Spillane, Sean O'Shea and Stephen O'Brien, Keane should always have at least three - if not four - players left in attack for their own kickouts. And they can win the ball without those players coming back for their own kickout - a mistake that so many make when they all get sucked in to helping out.

If nothing else, it will keep Dublin honest but Jim Gavin has displayed the cojones before to leave men unmarked in their own defence as long as the ball is on the opposition 13 and as long as they have an opportunity of turning the other team's kickout into a dangerous attack for themselves.

If Kerry win the ball, they're under pressure but, if they win it, there's generally enough space and time for Dublin to shift back and cover those loose men because the press is fluid and reacts instantly when the ball is kicked.

If nothing else, it will keep Dublin honest but Jim Gavin has displayed the cojones before to leave men unmarked in their own defence as long as the ball is on the opposition 13 and as long as they have an opportunity of turning the other team's kickout into a dangerous attack for themselves.

If Kerry win the ball, they're under pressure but, if they win it, there's generally enough space and time for Dublin to shift back and cover those loose men because the press is fluid and reacts instantly when the ball is kicked.

If Dublin have you every way then Kerry had better bring something different to their kickout game. The press won't be implemented on all the kickouts, it won't be there for 70 minutes but it's coming - probably from the start after its success against Mayo - and the Kingdom absolutely need a clear plan that's going to get them off the ropes.

If they don't have that, Dublin showed they have the potential to finish the match within 10 minutes.

There are three things Kerry can do to improve the success of their own kickouts against a zonal press, some of which haven't even been tried against Dublin yet.

If Dublin have you every way then Kerry had better bring something different to their kickout game. The press won't be implemented on all the kickouts, it won't be there for 70 minutes but it's coming - probably from the start after its success against Mayo - and the Kingdom absolutely need a clear plan that's going to get them off the ropes.

If they don't have that, Dublin showed they have the potential to finish the match within 10 minutes.

There are three things Kerry can do to improve the success of their own kickouts against a zonal press, some of which haven't even been tried against Dublin yet.

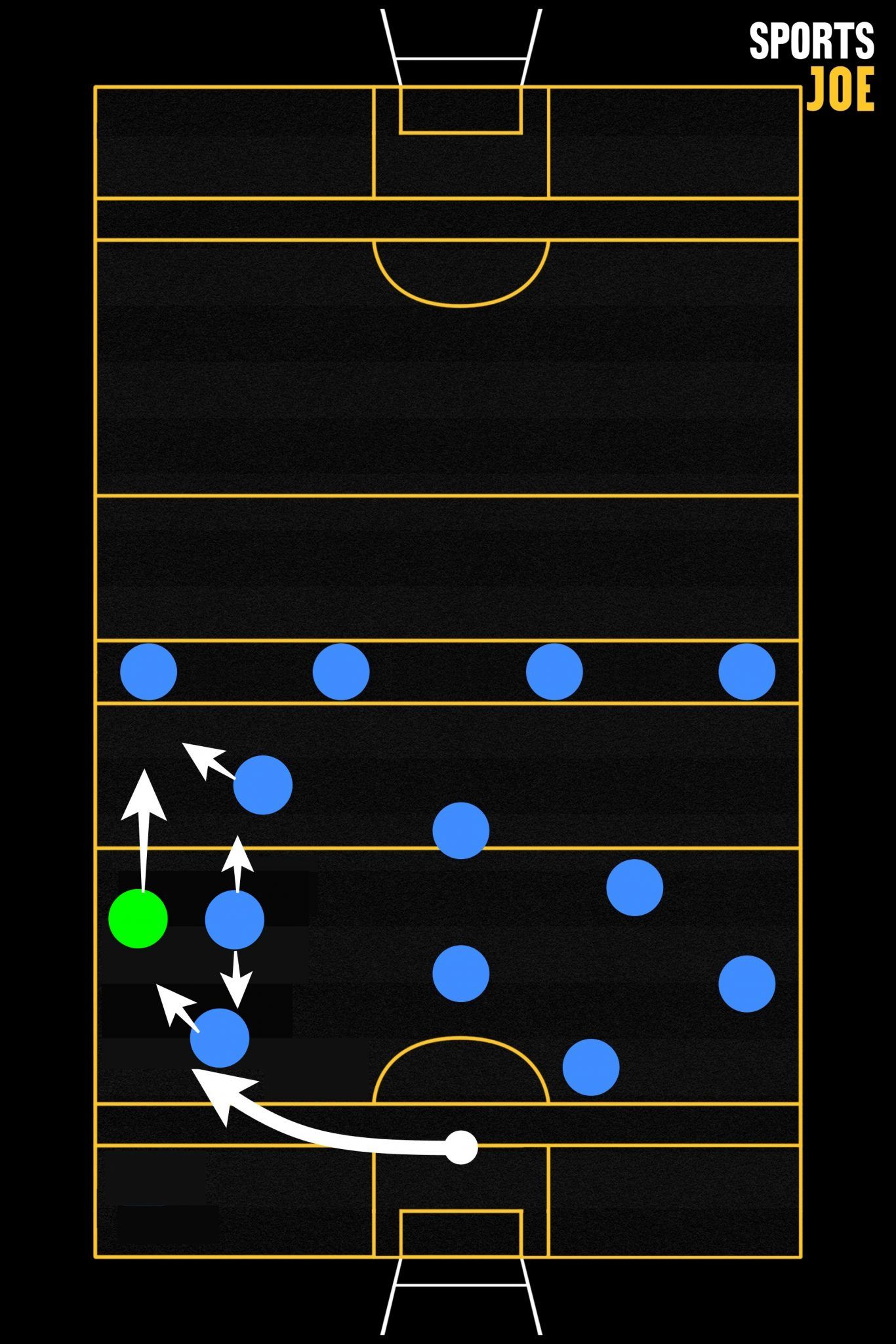

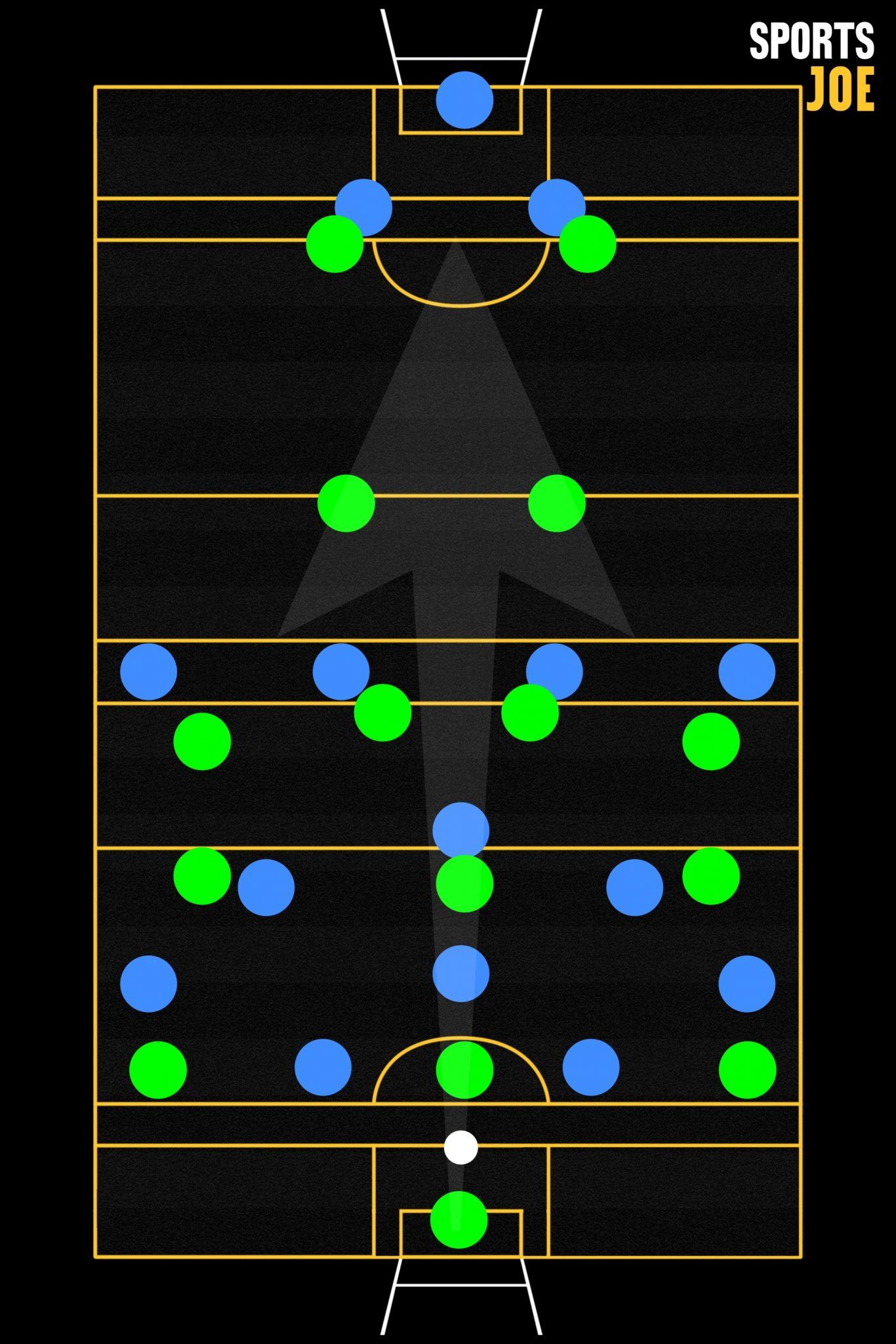

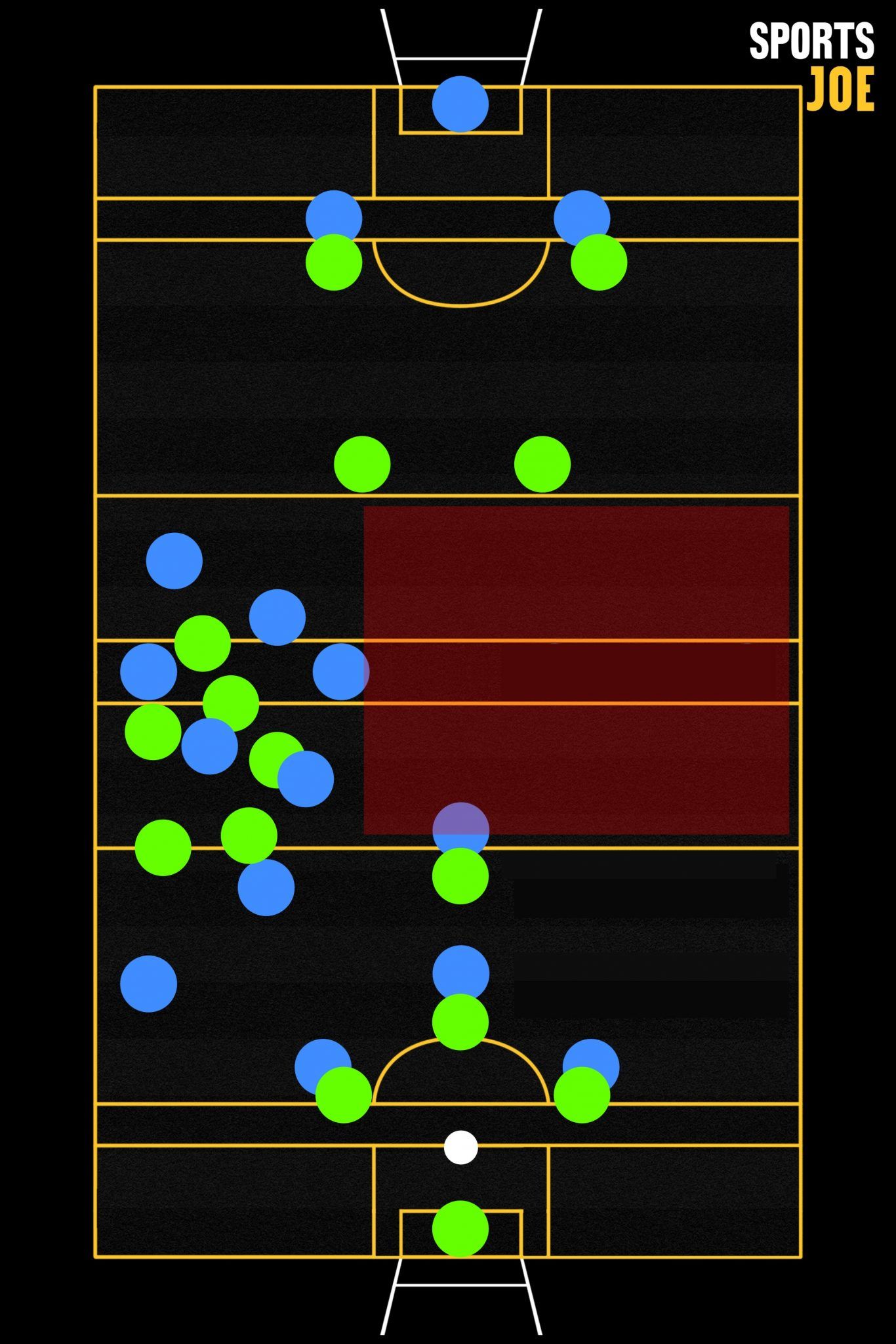

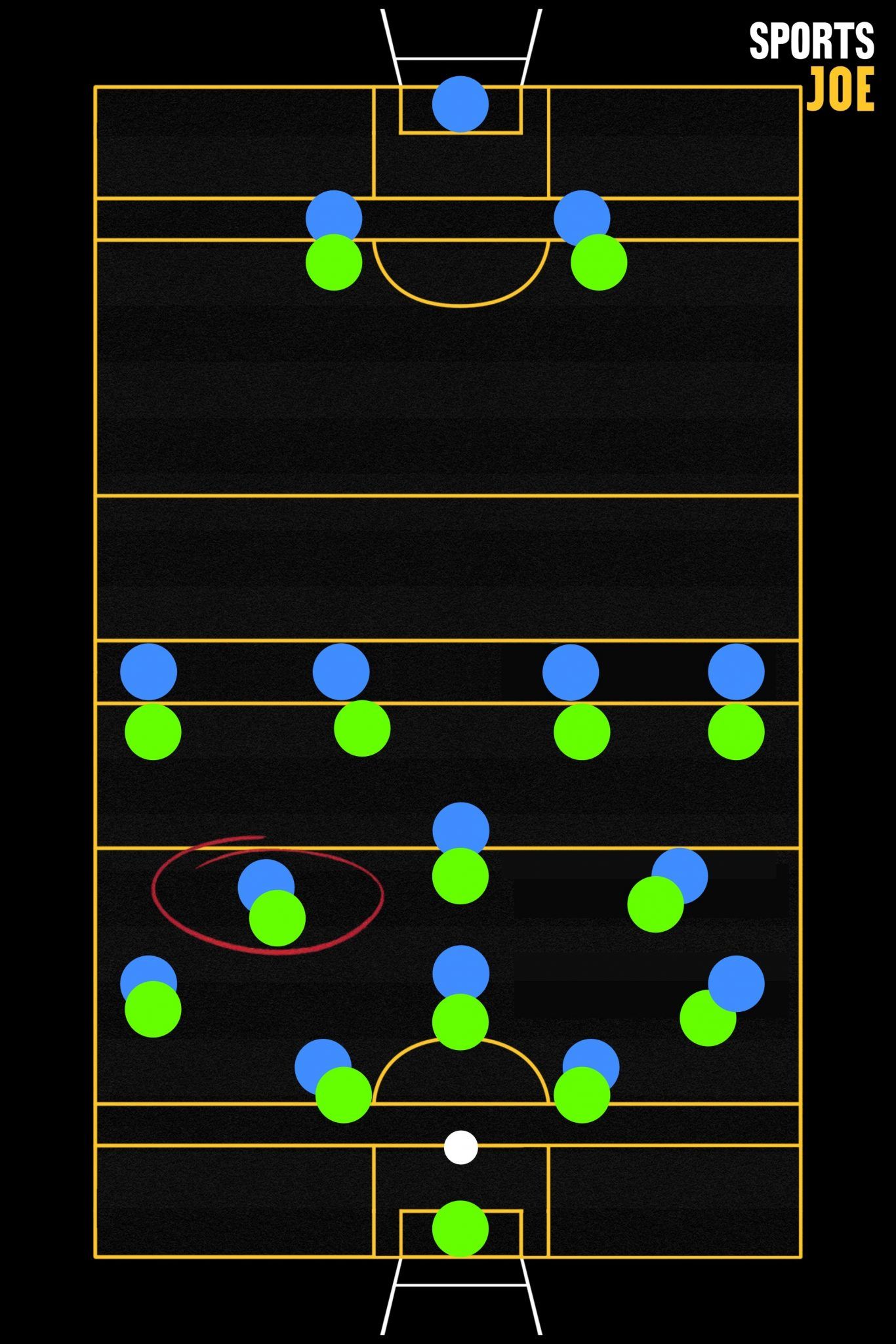

By simply vacating one side of the pitch, as many as seven Dublin men can be immediately taken out of their 12-man press, if of course they stay in those zones.

But that's exactly the question you want to start asking them.

By simply vacating one side of the pitch, as many as seven Dublin men can be immediately taken out of their 12-man press, if of course they stay in those zones.

But that's exactly the question you want to start asking them.

Three players are being marked by a full back line who aren't interested in the kickout and there are four more players covering one flank with no-one there to worry about. They can't affect the play if they stay there.

So, now, Dublin have a decision make.

They can either allow that overload to unfold and Kerry to have a massive numerical advantage on one side, or they react and join Kerry on the wing.

Three players are being marked by a full back line who aren't interested in the kickout and there are four more players covering one flank with no-one there to worry about. They can't affect the play if they stay there.

So, now, Dublin have a decision make.

They can either allow that overload to unfold and Kerry to have a massive numerical advantage on one side, or they react and join Kerry on the wing.

Either way, Kerry have put something back to Dublin.

Remember, this is the Kerry kickout, they should be the ones dictating the terms of the engagement but Jim Gavin's press has wrestled position and control away from most teams, even though it's their own set play.

With a simple overload, Kerry disrupt Dublin's zonal press. Either Dublin will give them the men over or they'll react and readjust their setup. Either way, Dublin are now being moved around.

That movement can create space.

Either way, Kerry have put something back to Dublin.

Remember, this is the Kerry kickout, they should be the ones dictating the terms of the engagement but Jim Gavin's press has wrestled position and control away from most teams, even though it's their own set play.

With a simple overload, Kerry disrupt Dublin's zonal press. Either Dublin will give them the men over or they'll react and readjust their setup. Either way, Dublin are now being moved around.

That movement can create space.

Does it mean Kerry can easily win ball in that space? Absolutely not. They're playing Dublin, for Christ's sake.

But at least they've given themselves a better chance and, as Mayo will attest to, all they need is to win a few balls and get them dead at the other side.

Had Paddy Durcan's shot gone over and not into Cluxton's hands during those 12 minutes, Mayo would've had a reprieve. They would've had a Dublin kickout to attack and pressure to exert further up the field. They would've given Dublin a problem again. Instead, they had to face the press seven times in a row and lost the game because they couldn't get out.

This way, it will be Dublin having to answer the questions and that does not happen anywhere near enough.

Does it mean Kerry can easily win ball in that space? Absolutely not. They're playing Dublin, for Christ's sake.

But at least they've given themselves a better chance and, as Mayo will attest to, all they need is to win a few balls and get them dead at the other side.

Had Paddy Durcan's shot gone over and not into Cluxton's hands during those 12 minutes, Mayo would've had a reprieve. They would've had a Dublin kickout to attack and pressure to exert further up the field. They would've given Dublin a problem again. Instead, they had to face the press seven times in a row and lost the game because they couldn't get out.

This way, it will be Dublin having to answer the questions and that does not happen anywhere near enough.

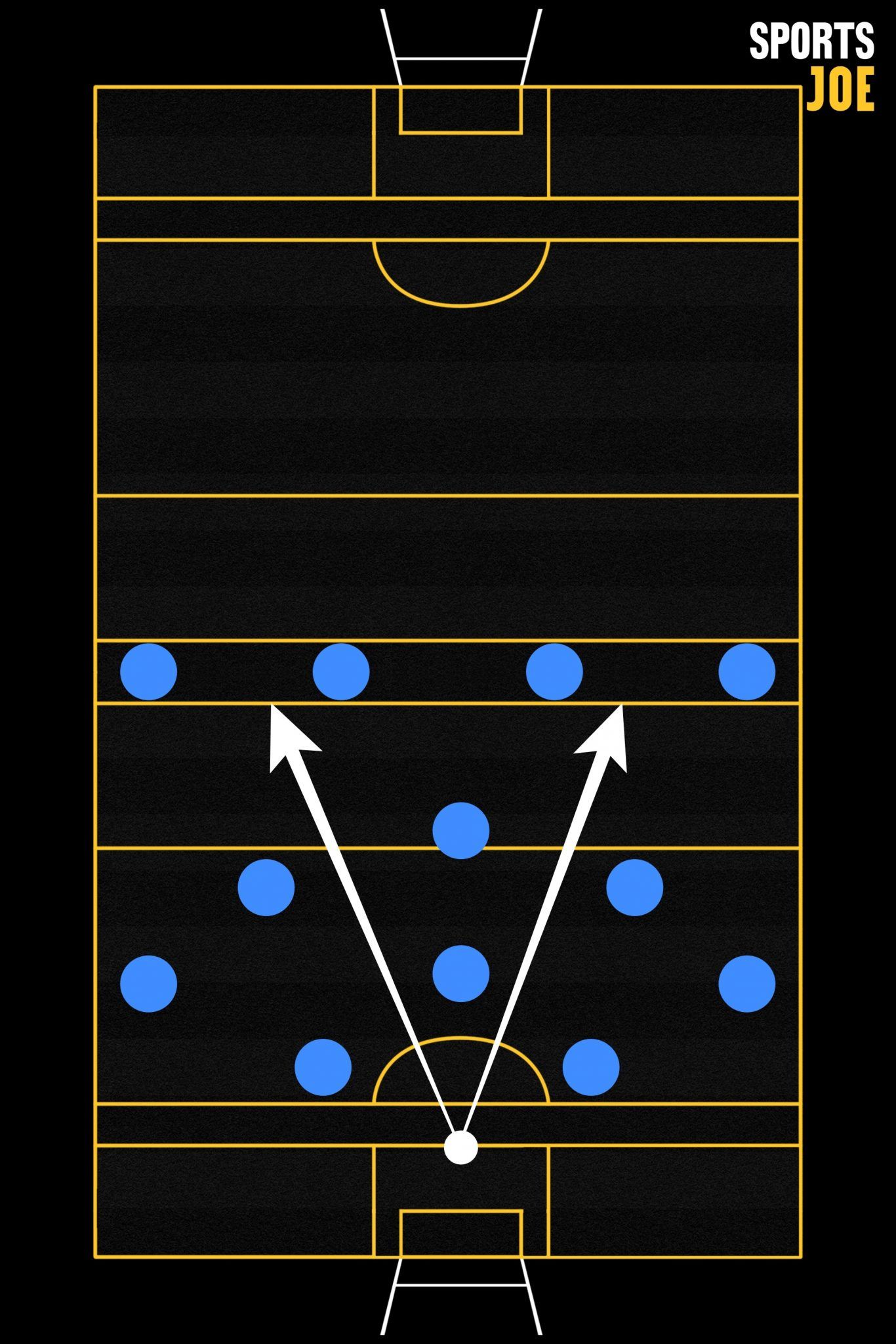

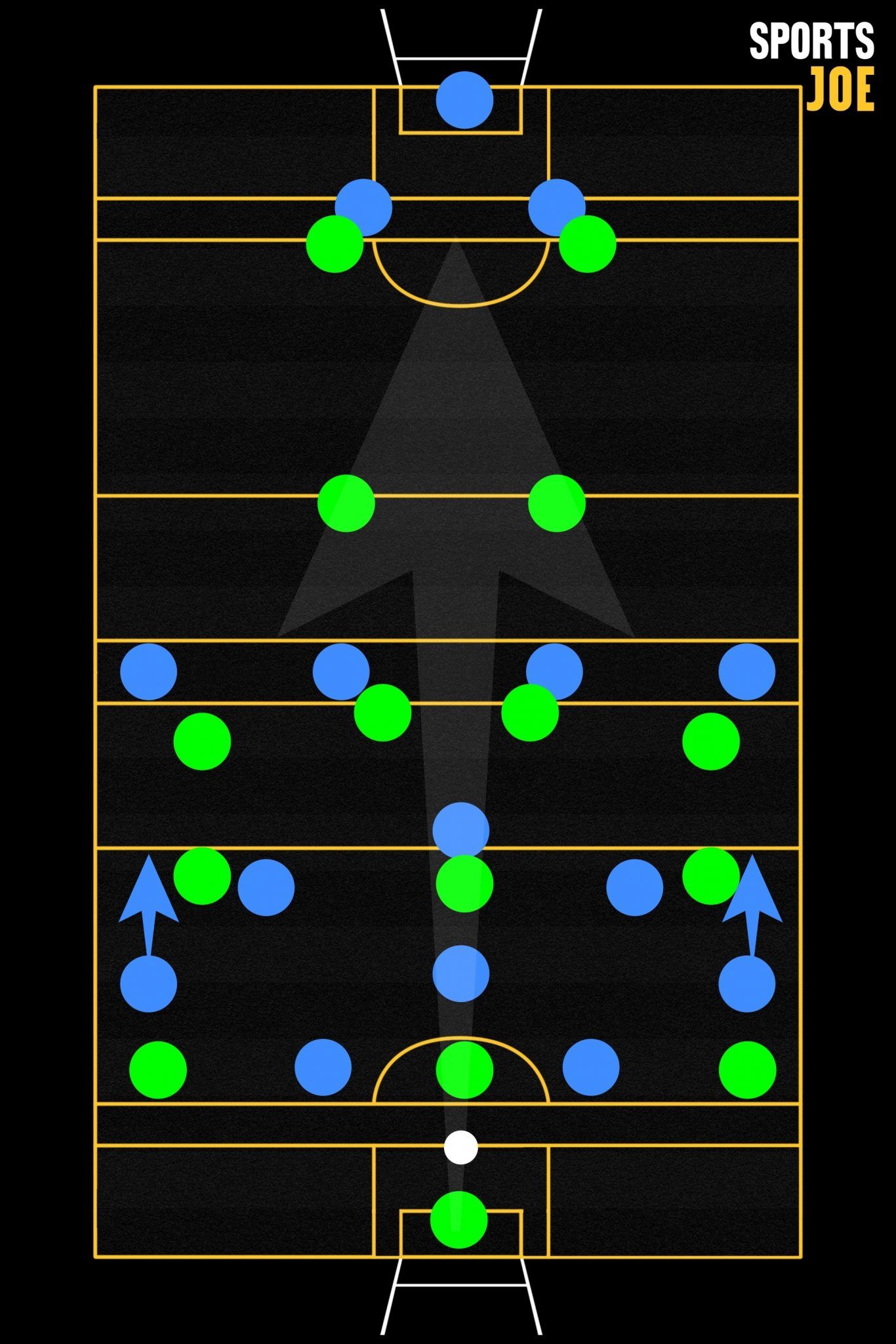

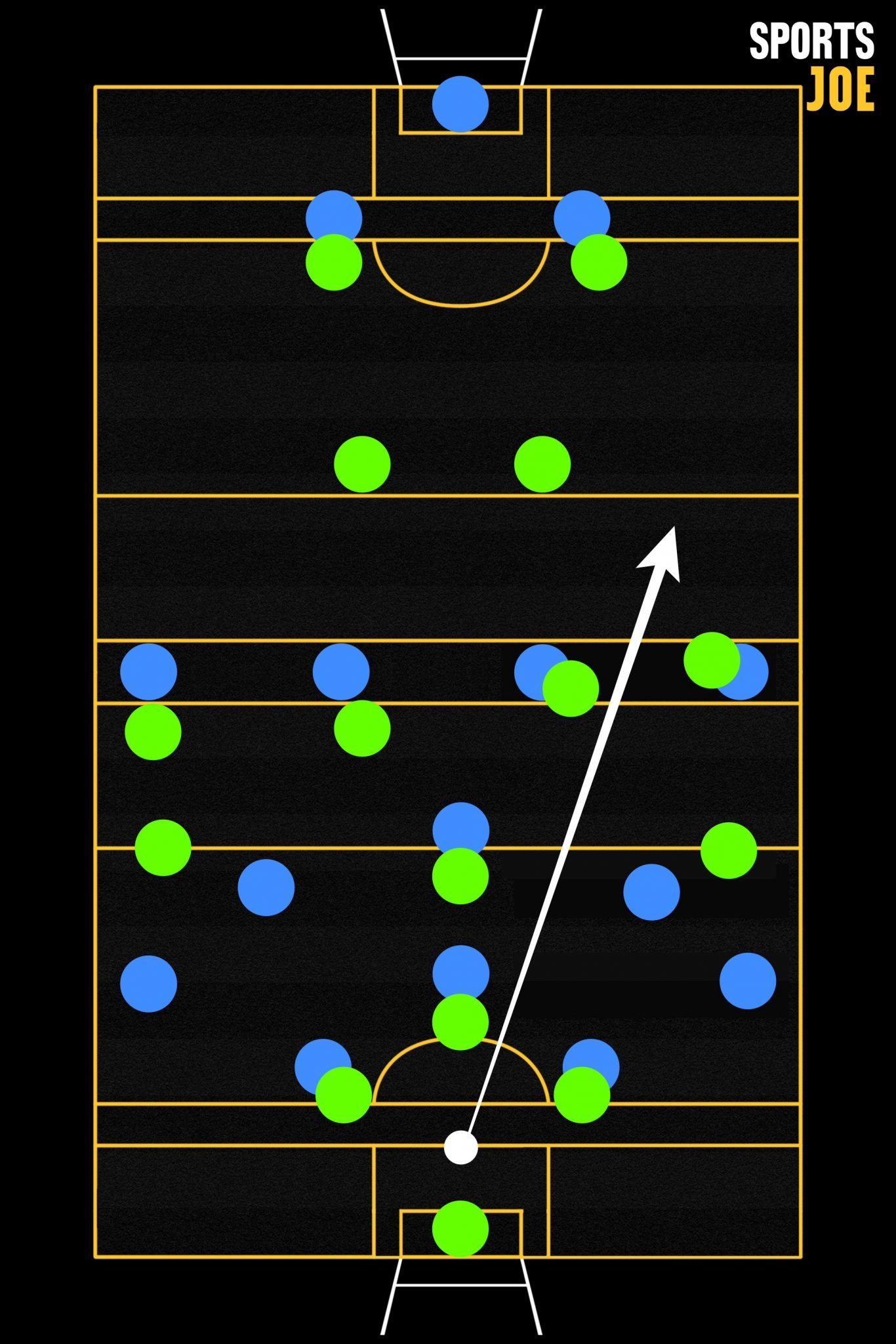

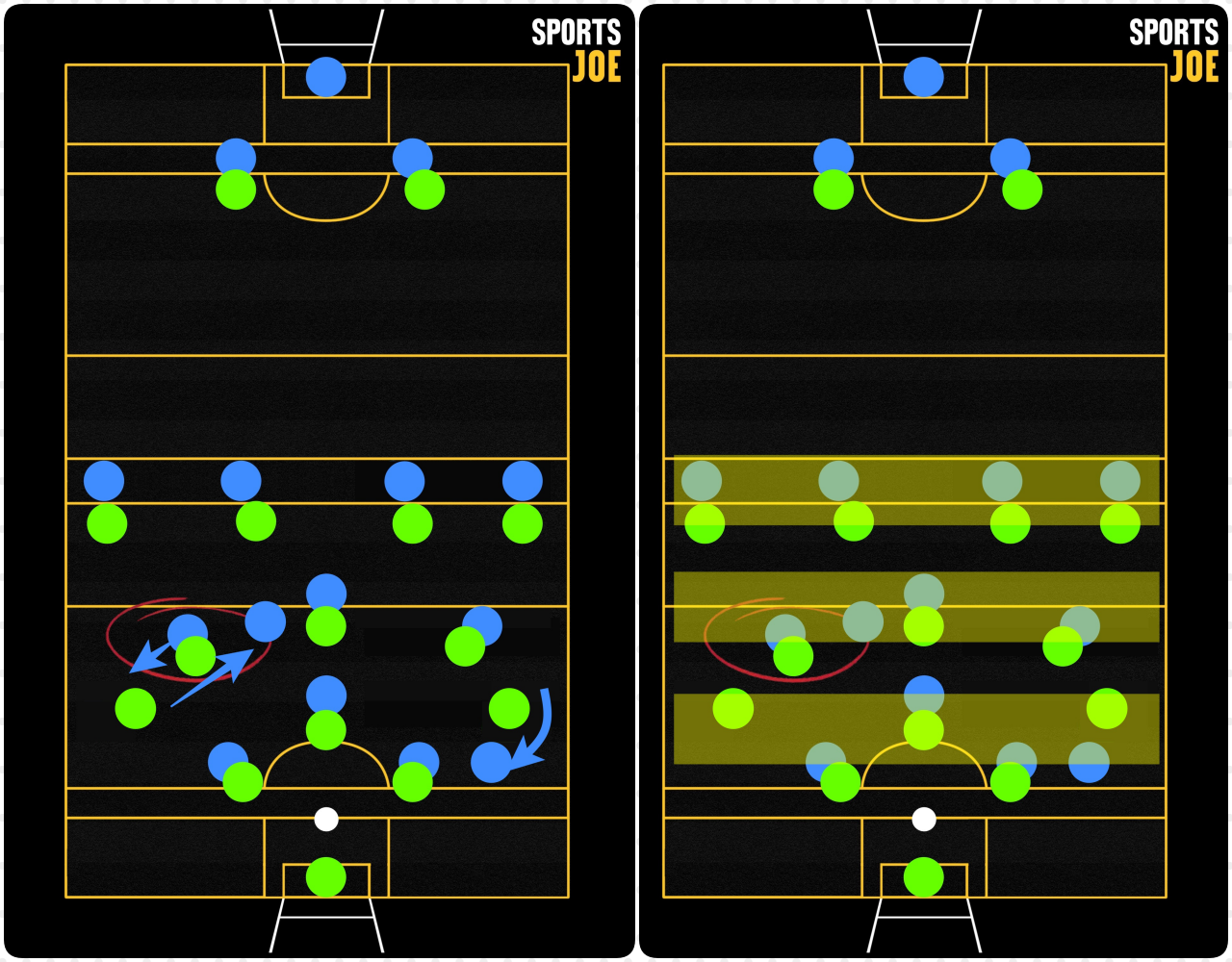

Shaun Patton, Rory Beggan, Stephen Cluxton could beat the Dublin press with their torpedo-like kicks and what that would instantly do is back Dublin off from committing to a full-on 12-man press.

If Kerry are keeping three or four forwards in position, there should be a wing forward free because Dublin will happily concede an attacker to complete their press. That spare man can be used as a weapon.

Kicking 65 or 70 metres is still going to allow The Wall to adjust and contest but the spare Kerry man can create an overload.

Shaun Patton, Rory Beggan, Stephen Cluxton could beat the Dublin press with their torpedo-like kicks and what that would instantly do is back Dublin off from committing to a full-on 12-man press.

If Kerry are keeping three or four forwards in position, there should be a wing forward free because Dublin will happily concede an attacker to complete their press. That spare man can be used as a weapon.

Kicking 65 or 70 metres is still going to allow The Wall to adjust and contest but the spare Kerry man can create an overload.

With the right kick, with the right trajectory, Kerry can create a 3 v 2 in Dublin's half. MacAuley and Howard or Fenton and McCarthy are still a good bet for Dublin in that scenario but, again, Kerry are giving themselves a chance and they're forcing Jim Gavin into reacting.

If Kerry keep those four players in attack and Gavin grows wary of any of them being free, then suddenly there's only 10 players instead of 12 committed to a press and Kerry are already facing a less daunting task.

With the right kick, with the right trajectory, Kerry can create a 3 v 2 in Dublin's half. MacAuley and Howard or Fenton and McCarthy are still a good bet for Dublin in that scenario but, again, Kerry are giving themselves a chance and they're forcing Jim Gavin into reacting.

If Kerry keep those four players in attack and Gavin grows wary of any of them being free, then suddenly there's only 10 players instead of 12 committed to a press and Kerry are already facing a less daunting task.

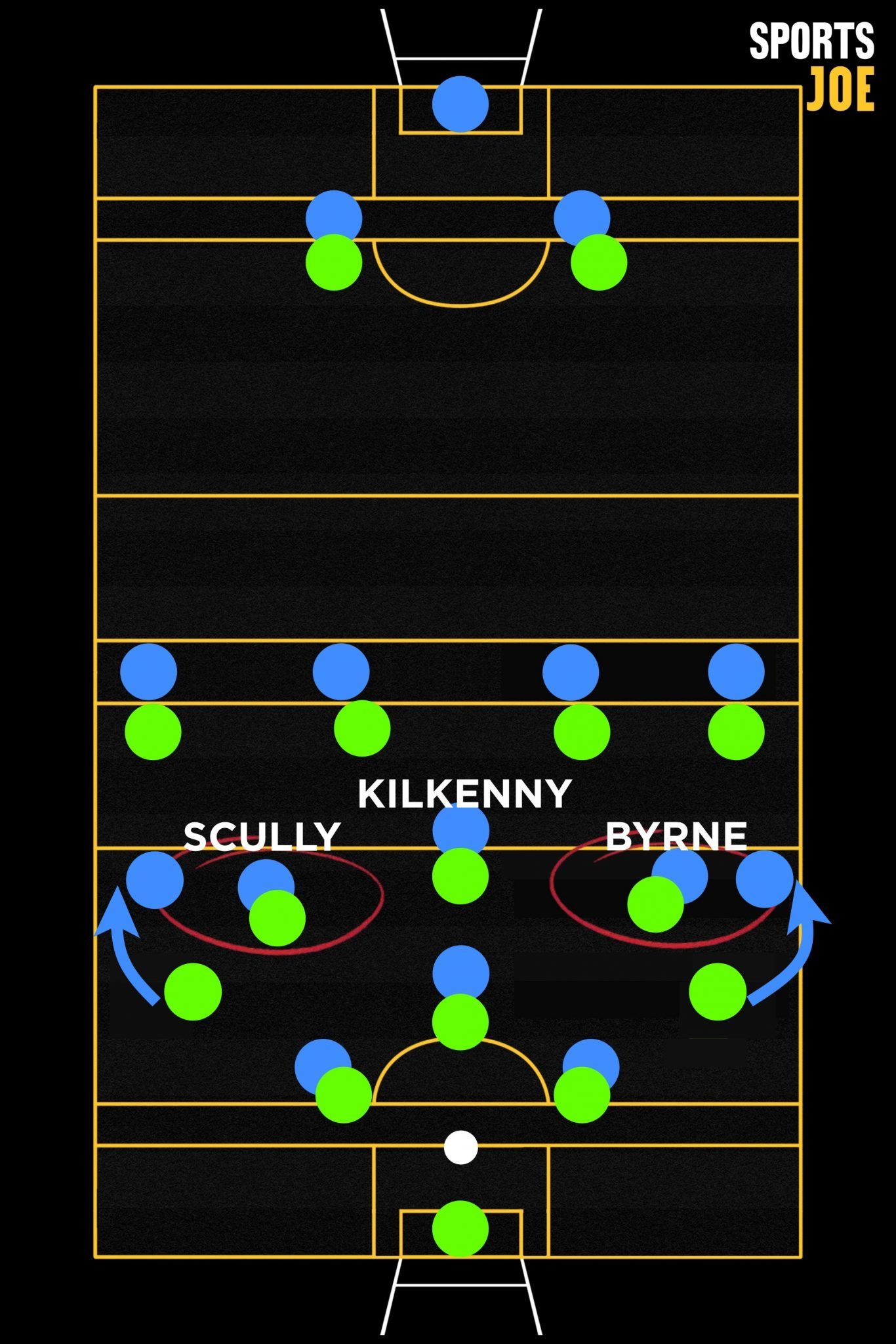

Take David Moran.

If Brian Fenton - during this squeeze at least - is stationed at midfield, Kerry can bring Moran into someone like Niall Scully's zone.

At that stage, it's still a toss up, it's a fight for the ball and Dublin will get players around - but every one of those players have a Kerry man detailed to them - and you'd still fancy Moran in a one-on-one with someone who's not Brian Fenton, MacAuley et al.

Take David Moran.

If Brian Fenton - during this squeeze at least - is stationed at midfield, Kerry can bring Moran into someone like Niall Scully's zone.

At that stage, it's still a toss up, it's a fight for the ball and Dublin will get players around - but every one of those players have a Kerry man detailed to them - and you'd still fancy Moran in a one-on-one with someone who's not Brian Fenton, MacAuley et al.

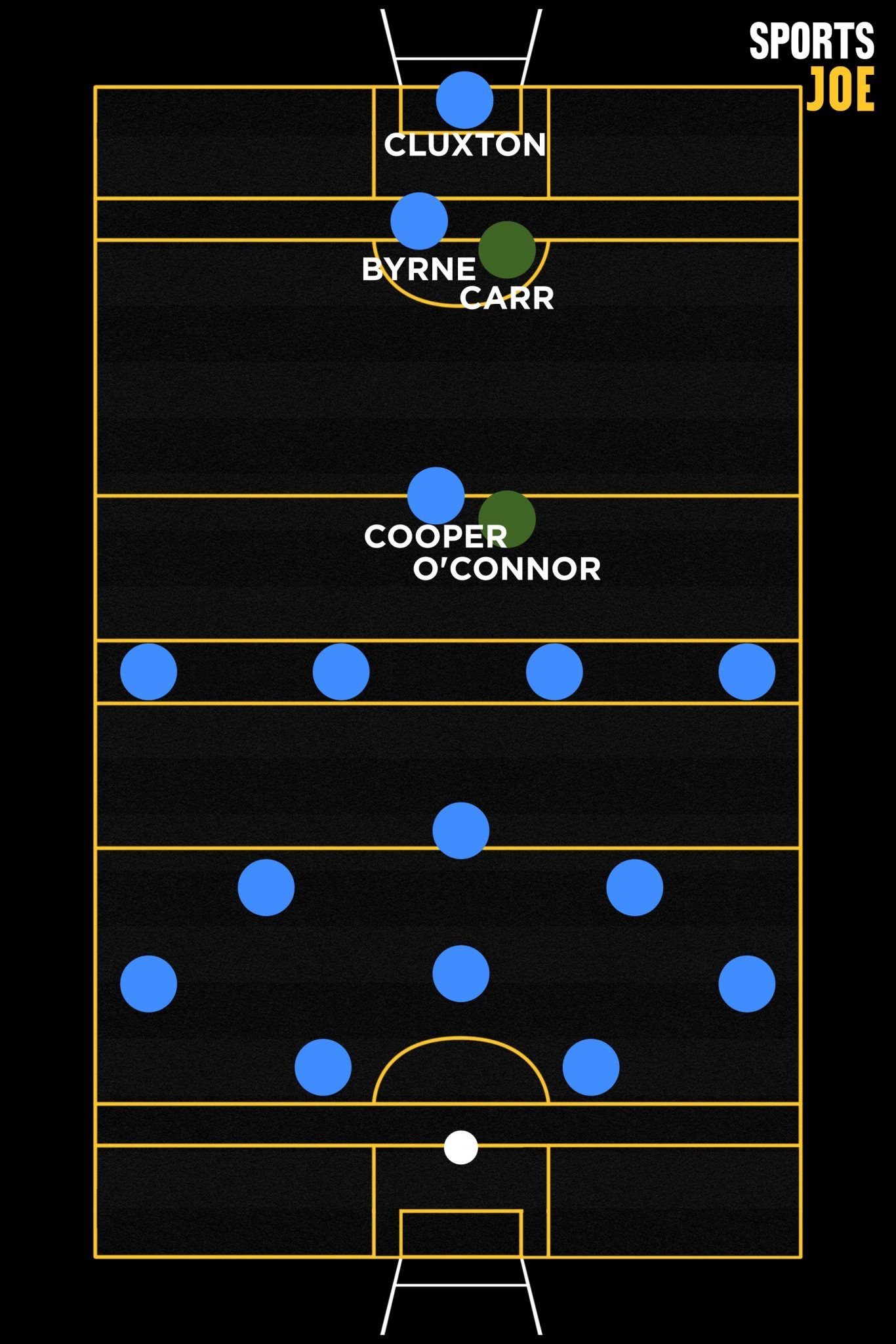

If Kerry are bringing everyone back to man up with the 12 Dublin players committing to the press, then they can create mismatches.

Say, for instance, Geaney and Clifford stay inside, Cooper and Fitzsimons will probably be detailed to stay with them. That leaves a full back pushing out - it was Fitzsimons or Cooper the last day pushing out against Mayo - but it could be Davy Byrne in the final if the other two are man-marking.

That extra full back helps form that middle five on the opposition 45' and, as a unit, it is frightening, almost immovable.

If Kerry are bringing everyone back to man up with the 12 Dublin players committing to the press, then they can create mismatches.

Say, for instance, Geaney and Clifford stay inside, Cooper and Fitzsimons will probably be detailed to stay with them. That leaves a full back pushing out - it was Fitzsimons or Cooper the last day pushing out against Mayo - but it could be Davy Byrne in the final if the other two are man-marking.

That extra full back helps form that middle five on the opposition 45' and, as a unit, it is frightening, almost immovable.

And they'll float to wherever they have to go to make the press even more difficult to navigate your way around.

And they'll float to wherever they have to go to make the press even more difficult to navigate your way around.

It shifts fluidly from a 4-5-3 to a 4-4-4 but either formation just means that Dublin are squeezing to death the midfield, the 45 and the full back line and they're forming road blocks for any kickouts or any passage out for the opposing defence.

It shifts fluidly from a 4-5-3 to a 4-4-4 but either formation just means that Dublin are squeezing to death the midfield, the 45 and the full back line and they're forming road blocks for any kickouts or any passage out for the opposing defence.

Trying to get through that for an entire game is draining and it's part of the reason - only part - why so many teams just fade physically against the champions.

Rather than trying to take it on in its strongest form, in its entirety, Kerry can divide and conquer and they can place their ball-winners in fancied one-on-one situations. The power of the press is almost Spartan-esque, the key is in its unbreakable unity. Kerry need to turn this facet of the game into individual duels. And they can.

Trying to get through that for an entire game is draining and it's part of the reason - only part - why so many teams just fade physically against the champions.

Rather than trying to take it on in its strongest form, in its entirety, Kerry can divide and conquer and they can place their ball-winners in fancied one-on-one situations. The power of the press is almost Spartan-esque, the key is in its unbreakable unity. Kerry need to turn this facet of the game into individual duels. And they can.

To do it though, the ball has to be good because Dublin are better than anyone at winning breaks so, whilst Shane Ryan's kicking is clean and accurate, he cannot allow them to hang like he did in the 71st minute against Tyrone. Dara Moynihan made a run into space, Ryan floated one up for him but because of its trajectory, it allowed Tiernan McCann to step back and intercept in the air before Moynihan could get a hand on it. Tyrone scored and suddenly there was just a goal in the game again.

Any ball to Moran in that situation - or to Sherwood or Adrian Spillane or Tommy Walsh - has to be crisp, sharp and leave no doubt that only two men will be fighting for that initial possession.

Obviously, Dublin will react to that. They won't allow David Moran to win high ball above men they don't want competing with him and the cavalry will soon arrive.

To do it though, the ball has to be good because Dublin are better than anyone at winning breaks so, whilst Shane Ryan's kicking is clean and accurate, he cannot allow them to hang like he did in the 71st minute against Tyrone. Dara Moynihan made a run into space, Ryan floated one up for him but because of its trajectory, it allowed Tiernan McCann to step back and intercept in the air before Moynihan could get a hand on it. Tyrone scored and suddenly there was just a goal in the game again.

Any ball to Moran in that situation - or to Sherwood or Adrian Spillane or Tommy Walsh - has to be crisp, sharp and leave no doubt that only two men will be fighting for that initial possession.

Obviously, Dublin will react to that. They won't allow David Moran to win high ball above men they don't want competing with him and the cavalry will soon arrive.

The benefit for Kerry there, of course, is that they will have broken up The Wall. The foursome that Dublin want to man the long balls at midfield isn't as strong as they want it to be anymore and, with a third option, Kerry have yet another way of turning the table on Dublin.

Man for man, Dublin will still fancy themselves but Dublin's press isn't a man for man marking job. It's a zonal squeeze that covers every piece of grass that they can, a structure where they can pass runners and individuals off to the next zone without having to chase or be dragged out of position or vacate any space.

Kerry can disrupt that and force Dublin into reacting or retreating. It's a Kerry set play and they should be the ones dictating the shape and the patterns that unfold from it.

Crucially, and very simply, if they can win some ball, they'll be doing what Mayo failed to do in that 12-minute period and putting it back on Cluxton's tee where Kerry can push up and attack, where the Dubs will be stretched and where they won't be allowed to set up camp with 12 men inside their half.

It's only one problem for Peter Keane - a massive one - but it created the period of the game that Dublin won the match against Mayo - in the other three quarters, they only won by a total deficit of one point.

Getting out of that trap would've given Mayo a much better chance of staying with Dublin and it's going to be the most important thing Peter Keane prepares for.

There are three things he can do in an attempt to get around what he knows is coming. And the mad thing about it is that these are things that nobody has even tried against Dublin yet.

The benefit for Kerry there, of course, is that they will have broken up The Wall. The foursome that Dublin want to man the long balls at midfield isn't as strong as they want it to be anymore and, with a third option, Kerry have yet another way of turning the table on Dublin.

Man for man, Dublin will still fancy themselves but Dublin's press isn't a man for man marking job. It's a zonal squeeze that covers every piece of grass that they can, a structure where they can pass runners and individuals off to the next zone without having to chase or be dragged out of position or vacate any space.

Kerry can disrupt that and force Dublin into reacting or retreating. It's a Kerry set play and they should be the ones dictating the shape and the patterns that unfold from it.

Crucially, and very simply, if they can win some ball, they'll be doing what Mayo failed to do in that 12-minute period and putting it back on Cluxton's tee where Kerry can push up and attack, where the Dubs will be stretched and where they won't be allowed to set up camp with 12 men inside their half.

It's only one problem for Peter Keane - a massive one - but it created the period of the game that Dublin won the match against Mayo - in the other three quarters, they only won by a total deficit of one point.

Getting out of that trap would've given Mayo a much better chance of staying with Dublin and it's going to be the most important thing Peter Keane prepares for.

There are three things he can do in an attempt to get around what he knows is coming. And the mad thing about it is that these are things that nobody has even tried against Dublin yet.

Explore more on these topics: