Ever since be became Liverpool’s first black player in this month 36 years ago, Howard Gayle has been seen as a trailblazer for the community he came from.

It isn’t a view he shares. Where he led, few others have followed and for those who have their impact has been minimal. Black players are no longer a novelty at Anfield but those who share Gayle’s background remain conspicuous by their absence and it troubles him.

In truth, it is something that has nagged at Gayle since his playing days when he would see talented players from Liverpool 8 taken on trial at the club where he first made his name only for all of them to fall by the wayside.

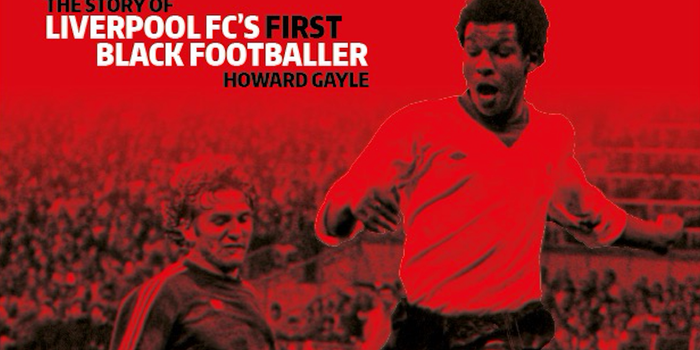

But it was only when researching his autobiography, 61 Minutes In Munich: The Story of Liverpool FC’s First Black Footballer, that he realised just how limited the impact of Liverpool’s black community, the oldest in the country, has been at Anfield.

“I discovered that in Liverpool Football Club’s history, only three players from the local black community have represented the club, making a total of sixteen appearances between them. I find that astonishing,” Gayle says.

Liverpool FC

Local Lad

Howard Gayle pic.twitter.com/hZyt6nTFbV— Superb Footy Pics (@SuperbFootyPics) September 29, 2016

“People say I was a groundbreaker but how can that be true? The next one after me was Tony Warner, a goalkeeper who holds the record for most appearances on the subs bench without getting on the pitch and then there was Jon Otsemobor and Lee Peltier.”

To put those collective sixteen appearances in perspective, at the age of 18 Marcus Rashford has already exceeded that total for Manchester United.

Marcus Rashford’s progress at Manchester United is in stark contrast to homegrown black players at Liverpool (Photo by Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

Marcus Rashford’s progress at Manchester United is in stark contrast to homegrown black players at Liverpool (Photo by Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)Both anecdotally and statistically, Gayle believes his concern is justified but he also believes that this isn’t a case of overt racism, reasoning that while there was a time in the past when black players were not as welcome as they should have been, there are now a variety of factors conspiring to prolong a situation of which his own emergence was supposed to have signalled the beginning of the end.

“Thinking back, I took my best mate, Steven Skeetes, in to Liverpool,” Gayle recalls. “Michael Owolabi, Michael Iho, we called him the gaffer because of the way he ran games, he was like a black Graeme Souness, went in too. Rod McDonald went in there, so did Neil Clarke. These were all good, hungry players and all they needed was a bit of development and coaching but I just got the impression that I was one too many.

“Looking back, I think the club could have done so much more than it did but because of its success no one could question their approach. How could they? No other club could get near them.

“The club was a successful juggernaut and maybe it’s only now that it sees that it has to change its philosophy. It’s never had to in the past. Although I have gripes about my time at the club you can’t argue with the success that it had. But I’ve always asked the question as a fan and as a player, if I was the first why has no one followed in my footsteps? Even from a coaching perspective, there hasn’t been the kind of involvement that you’d hope for with the people of Liverpool 8.

“The club knows about the work that I do in that community and you would have thought that someone would have approached me to be a part of things in some way but that’s never happened.

Great to meet Howard Gayle first #LFC black player, who put Tommy Smith in his place, at #lpc16 @SRTRC_England pic.twitter.com/y81Ftk7GHy

— Steve Howell (@FromSteveHowell) September 27, 2016

“Again, that makes me ask a question – if there are no back coaches, how can a young black player go to a coach to complain if he’s a victim of racial abuse, how can he be comfortable with that? These are real issues.

“Maybe young black players have felt uncomfortable. They might have looked at the opportunity to play for Liverpool and to pull on that red shirt, because most of the young kids in Liverpool 8 are Liverpool fans, and maybe looked at my history but the reality hasn’t been what they’ve hoped for.

“I don’t know why the club wouldn’t look at issues like this because when you look at its history, the dynamics of the city and the places it draws its support from home and abroad, it beggars belief. It’s a question that needs to be asked within the club.

“I’m 58 now and I think the club has missed out on making something of my links with the community in Liverpool 8 and there’s no one else to follow in my footsteps because there hasn’t been any other players from my background except maybe Tony Warner.

“My worry now is that the dynamic is starting to change. Young black kids are inspired by black role models and if they aren’t finding them at Liverpool then they will find them somewhere else.

“Liverpool currently has no local black players so that connection isn’t there and that means black Liverpool kids can just as easily find role models at Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester United or whoever as they can at Liverpool. That weakens the link that’s always been there and that can’t ever be a good thing.

“It isn’t just about race though. We now seem to have more kids coming through the academy and getting close to the first team or the under-23s who are from places other than this city.”

With Howard Gayle at Show Racism the Red Card meeting today @SRTRC_England #Lab16 #Legend pic.twitter.com/IWPJS89wLj

— Marsha de Cordova MP (@MarshadeCordova) September 26, 2016

It is here that Gayle believes any scrutiny of the issue needs to be widened to take into account Liverpool’s relationship with its host community as a whole. “I think it’s broader than race,” he argues. “I think it’s about how the club interacts with its own city. I have always said that I would stack 11 Scousers up against anyone, it doesn’t matter whether they are white, black or whatever.

“You take eleven kids from this city who know the philosophy of Liverpool – what I mean by that is Scousers don’t play friendlies, they are naturally competitive – and put them up against anyone and they will hold their own at the very least. We’ve just lost two like that in Steven Gerrard and Jamie Carragher and that’s what you miss. It’s about recognising the talent and the raw material on your own doorstep.

“If kids from this city are mentored and nurtured in the right way and four or five of them get into Liverpool’s first team that club would take off. Why are we going all over the world bringing players into the academy who aren’t getting into the first team? That’s what makes it so sad that there are no Scousers in the team now.

“I coach in my own community and I see good players but too often when these kids get a chance at the club they fail. The question needs to be asked why this keeps happening? It’s a travesty.

“I’ve thought for some time that Liverpool is one of the few places in the world that could do what Barcelona do with their youth setup by giving priority to local kids and only looking elsewhere in extraordinary circumstances. If you filled your team with Scousers you might not win every game but you know that you’d get value for money and you know they’d give everything for the cause.

“But going down that route would involve breaking the status quo and thinking differently and clubs don’t seem willing to go against the grain.”

One of the tragedies of Gayle’s career, although he sees the positive side of it too, is that it is defined by race. Despite being a European Cup winner who was also one of the goalscorers when England won the European under-21 Championships in 1984, Gayle’s talent and achievements have tended to be forgotten. Whereas Graeme Souness was a great captain, Kenny Dalglish a great player, Phil Neal a great full back and Alan Hansen a great centre back, Gayle was a black footballer.

By his own admission, Gayle was not a great and his career became closer to that of a journeyman after he left Liverpool, but nevertheless it is his colour that people tend to remember most, not what he could or couldn’t do with a football.

In a long career, Gayle played more than 100 games for Blackburn Rovers (Photo by Russell Cheyne/Allsport)

In a long career, Gayle played more than 100 games for Blackburn Rovers (Photo by Russell Cheyne/Allsport)

“All I ever wanted to be was Howard Gayle, footballer but that was never going to be allowed to happen,” Gayle insists. “It was when I got onto the fringes of the first team that I began to be identified as the club’s first black player and that defined me from that point on.

“Because I stood out and because I was different that sometimes made things more difficult for me than they should have been. There is no question about that.

“My two brothers, who I have the utmost respect for, used to always say to me that I had to be better than the white players, maybe twice as good, because if not I would be the one who’d be criticised if things didn’t go right. Looking at the way things are, even to this day, I’d have to say that they were right.”

That perception lingers to this day. The title of his book refers to the 61 minutes that Gayle spent on the pitch in the second leg of Liverpool’s European Cup semi-final away to Bayern Munich in 1981. On that occasion, Dalgish was forced off through injury after just seven minutes.

Gayle’s big moment had arrived. Brought on as substitute by Bob Paisley, he recalls falling victim to several fouls before making one of his own on Wolfgang Dremmier, the Bayern defender, for which he was booked. Within three minutes of receiving the yellow card, Gayle himself was replaced, a decision by Paisley which has rankled ever since, although his respect for the legendary Liverpool manager remains strong.

“Had it been Souness would he have been taken off? No. He was trusted and I wasn’t,” Gayle states.

“After the game Bob Paisley gave an interview where he said they had wanted to avoid going down to ten men with the game possibly going to extra time but that comes down to a lack of trust. Maybe he thought that the referee was looking to send me off but I was really disappointed because I thought I had a lot still to offer in that game.

“Even now when I look at the pictures from that night I can see Ronnie Moran trying to console me but I was too dejected to take it in.

“I think that the club didn’t trust me. I think they saw me as an uncontrollable hot head and that if someone said the wrong thing to me I would react in a manner that might have got me sent off. I only got sent off twice in my entire career though. Once was at Newcastle for calling the referee a cheat after I’d already been booked.

“The other time was in a reserve game against Bury and one of their players, a Scouser funnily enough, called me a n****r and then went to call me a black c**t but I’d hit him before he’d got all of the second word out.

“The referee heard it and sent both of us off. I had to go and see Bob Paisley on the Monday morning and I thought he’d be fuming because Liverpool hated players being sent off.

“But he said to me that the only reason that people were going to come for me in that way and say these kind of things to me was that I am a good player and the only way they could stop me would be by getting me to do what I’d done. I learned from that. I was always controlled.

Bob Paisley gave Gayle some good advice (Photo by Getty Images/Getty Images)

Bob Paisley gave Gayle some good advice (Photo by Getty Images/Getty Images)

“That game in Munich, I committed one foul and the referee decided to book me because he’d booked three or four players for challenges on me. I don’t think I was ever in danger of being sent off.”

On August 8 this year, Gayle received a phone call from Ged Grebby from Show Racism The Red Card who informed the son of a seafarer from Freetown, Sierra Leone and maternal grandson of Ghanaians, that he had been nominated for an MBE. Grebby was in no way surprised when Gayle rejected the honour, saying “I knew you would.”

Two months on, it is a decision that he in no way regrets. “No, because of what the MBE represents,” Gayle says.

“I have campaigned, one way or another, against racism all my life. I’m acutely aware of black history and the slave trade that not only touched here but places all over the world and I am also aware of the atrocities that were committed against black people during that time.

“On top of that, I am aware of the role played by the British Empire. Accepting that medal, one bearing the title Member of the British Empire, would have said that I was a member of their club. How could I accept it?

“I was always mindful that because I’d been given awards by my own community and because I’m an ambassador for Show Racism The Red Card and Kick It Out that the day might come when I might be offered this kind of award. But the answer, if it did happen, was always going to be ‘No’.

“So when the offer did come it felt like an insult. It would have been a betrayal of those poor souls who not only suffered during the slave trade, more than ten million were murdered.

“People from my background are always being told that we should move on and in my own case I can say that I have moved on but how could I possibly forget that it happened? It’s a part of my personal history and it’s also a part of black history and black culture and it will be something that is part of my thinking until the day I die.

“It’s not about resentment as some claim, it’s about using that history and what we have learned from it to try and make sure that this world is a better place for our children and grandchildren.”

In keeping with that objective, Gayle also wants his beloved Liverpool to do more to embrace not only the black community from which he came but also other areas of his home town that he fears are in danger of being left behind as the football industry continues to spread its net further and wider in search of both footballers and those who pay to watch them. Again, the point he is making is not about race, it is about community and identity.

“Liverpool is my club,” he says. “I’ve gone home and away with them, I’ve been fortunate enough to play for them and Anfield is probably the single place I’ve visited most in my life. The hairs on the back of my neck still stand up when I turn up Oakfield Road and see the ground on the horizon. I’ve been through the full gamut with that club and I love it.

“I want it to be successful again and I want it to be as inclusive as it possibly can be. I want to see more kids from all the different districts of the city on the pitch and in the stands. Then it will be a club that people like me can identify so much more.

“Over the last four or five years genuine fans have been priced out of going to watch their local club. That can’t ever be right.

It was a great honour yesterday meeting @LFC first black player #HowardGayle. A top man, very friendly and a gentleman. #YNWA #LFCvHCFC pic.twitter.com/Fee2Pj87ZG

— Joe Kasolo (@JoeKasolo) September 25, 2016

“The club is increasingly gearing itself towards corporate fans and I’m not saying there is no place for that because you have to compete but it should always remember that the success Liverpool has had over the years has been built on the unequivocal support it has had over the years. Everyone goes on about those special nights – St Etienne, Chelsea, Dortmund, but they were all made possible by the fans.

“There’s something special in that ground that no other club has got and I swear that when the people of this city turn up in great numbers, showing the passion that they have, it seems like Liverpool are almost unbeatable; you could put eleven bins out there in red shirts and they would win.

“Liverpool were nowhere near as good as Chelsea in 2005, they were champions and we were miles off them, but that night they felt the passion and couldn’t live with it.

“This is what the club has to harness. It’s not about fleecing the fans, it’s about listening to them and giving them the chance to show how special they are and how special this city is. I think the owners know about this but they just haven’t worked out how to make the most of it yet. There are times now when going the match feels like getting on a bus: you buy your ticket, you sit down and you get told to enjoy the ride.

“That’s not what it should be about. It should be about supporters being given the opportunity to come together and make a difference both to the atmosphere and to the team. That’s the way it always was at Liverpool, that was what made the club great and, when it comes down to it, that’s what we all want.”

![61 Mins cover copy[1]](https://dus09vr7ngt46.cloudfront.net/uploads/2016/10/05140949/61-Mins-cover-copy1.jpg)

61 Minutes in Munich, the Story of Liverpool FC’s First Black Footballer (deCoubertin Books) is available now.

WATCH: Liverpool BOTTLED the title race 🤬 | Who will win the Premier League?