Football

Share

Published 18:08 28 Apr 2021 BST

Updated 18:28 28 Apr 2021 BST

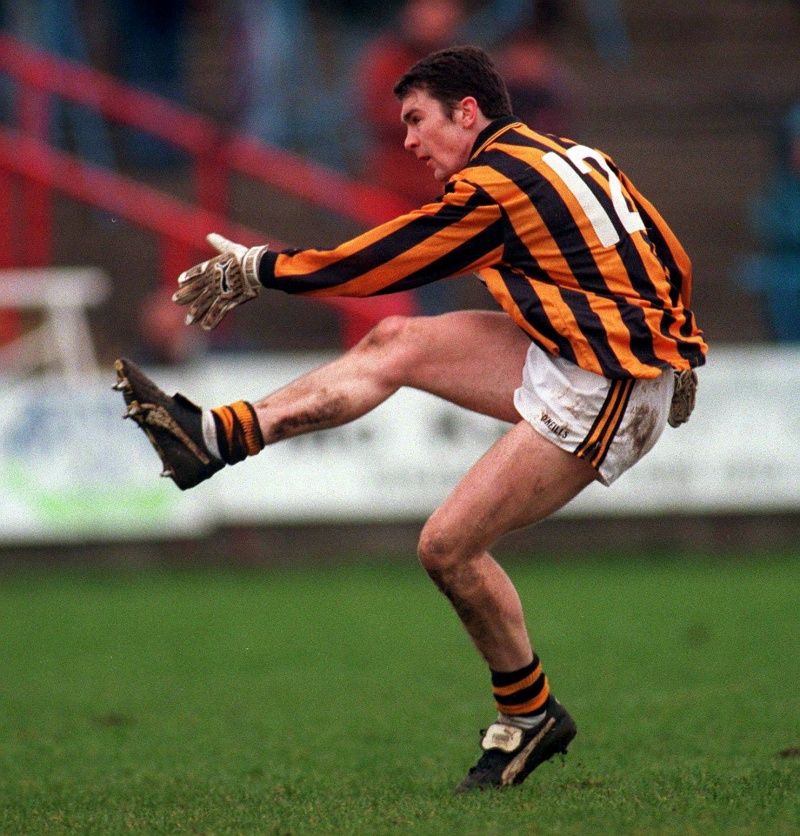

McConville scored the decisive goal in the 2002 All-Ireland senior football final while at the height of his gambling addiction.[/caption]

"I understand that, as a team or as a group of lads - a lot of lads will come together and give each other tips and have a bet and they'll do whatever - there is a lot of banter and a lot of craic in that. When I started off for example, it was great craic, I was having great fun.

"One of the reasons it's such a part of the GAA culture that if you're playing any sort of high level sport, then alcohol and drugs are usually taking a major back seat, especially during the season. And people see gambling as a harmless pass-time if that's the best way to put it.

"It's the crux of a lot of the conversations that go on on buses and in changing rooms up and down the country and WhatsApp groups is dominated by it. Yeah, I think it's very prevalent within sports teams."

Gambling is no black and white thing and for McConville, that's the most dangerous thing about it. Because for every four or five people who'll only bet at Cheltenham or at Punchestown using money they can afford, there's one with a serious problem just blending into the crowd.

It's that fine line between having the craic and having a problem that makes it so life-changingly important, according to McConville, that those who are suffering speak up.

That's why he's hear to spread the message about Extern Gambling Problem's phone-line, set-up to provide an easy to use service for those struggling in silence.

"Once that fun disappeared, I still continued to gamble.

"For every group of those lads," McConville says matter-of-factly, "there is one or two within that group who are really, really struggling. I can guarantee you that."

He's reflecting on his own problems just now.

"As gamblers, a lot of our thoughts are internal thoughts, they're hidden. For example, if I tell myself I'm an arsehole, I'm probably going to maintain that I'm an arsehole. Or if I tell myself that my gambling is normal, then my gambling is normal.

"But if I put something out there, I mean, when I admitted I had an issue, I started talking to my family about it. I honestly wasn't sure that I was addicted, even though it was obvious that I was, but it was only when I started voicing what was happening in my life, as far as emotions, finances, relationships and all that - it was only then when people were giving me feedback on it, and then I knew that my thoughts were completely illogical on it."

McConville scored the decisive goal in the 2002 All-Ireland senior football final while at the height of his gambling addiction.[/caption]

"I understand that, as a team or as a group of lads - a lot of lads will come together and give each other tips and have a bet and they'll do whatever - there is a lot of banter and a lot of craic in that. When I started off for example, it was great craic, I was having great fun.

"One of the reasons it's such a part of the GAA culture that if you're playing any sort of high level sport, then alcohol and drugs are usually taking a major back seat, especially during the season. And people see gambling as a harmless pass-time if that's the best way to put it.

"It's the crux of a lot of the conversations that go on on buses and in changing rooms up and down the country and WhatsApp groups is dominated by it. Yeah, I think it's very prevalent within sports teams."

Gambling is no black and white thing and for McConville, that's the most dangerous thing about it. Because for every four or five people who'll only bet at Cheltenham or at Punchestown using money they can afford, there's one with a serious problem just blending into the crowd.

It's that fine line between having the craic and having a problem that makes it so life-changingly important, according to McConville, that those who are suffering speak up.

That's why he's hear to spread the message about Extern Gambling Problem's phone-line, set-up to provide an easy to use service for those struggling in silence.

"Once that fun disappeared, I still continued to gamble.

"For every group of those lads," McConville says matter-of-factly, "there is one or two within that group who are really, really struggling. I can guarantee you that."

He's reflecting on his own problems just now.

"As gamblers, a lot of our thoughts are internal thoughts, they're hidden. For example, if I tell myself I'm an arsehole, I'm probably going to maintain that I'm an arsehole. Or if I tell myself that my gambling is normal, then my gambling is normal.

"But if I put something out there, I mean, when I admitted I had an issue, I started talking to my family about it. I honestly wasn't sure that I was addicted, even though it was obvious that I was, but it was only when I started voicing what was happening in my life, as far as emotions, finances, relationships and all that - it was only then when people were giving me feedback on it, and then I knew that my thoughts were completely illogical on it."

If a lack of self awareness was his problem back then, McConville has come full circle now.

"I'm not sure if people want to listen to ex-gamblers, if you know what I mean. I'm thinking that they feel as if the message might be a bit skewed."

This message hits right down the middle. Just like his frees did, which is quite the achievement, given the demons he was battling throughout his playing career with Armagh and Crossmaglen Rangers.

"I enjoyed the responsibility. People around me didn't enjoy it, they were more nervous about what I was doing than I was.

"My Mum used to always say, 'Don't bother with the penalties.' She felt there was too much pressure with them.

"But I enjoyed that responsibility. I suppose I was very used to it and a coach told me something when I was about 14 or 15 which helped me. I was devastated after missing a free-kick and he just called me aside and said, 'Listen if you're going to take free-kicks, you have to realise that you're going to miss some," adds McConville, who works for Sporting Chance, an addiction foundation set up by Arsenal footballer Tony Adams.

With McConville, the war-stories, as he calls them, only become more and more engaging.

"We used to train in Armagh and there was a guy who used to turn the lights off at the end of the night whenever we were finished training. He used to blast them to get me off the pitch because I would be the last person.

"People used to think I was very diligent but my life was in a mess at that stage, and I hated getting back into the car because I knew I'd be going back to my normal life and the phone calls from people that I owed money to.

"A lot of the practice I was doing was just to stay out of that car because I didn't want that side of my life to continue on."

It's hardly any surprise, given his knack for cracking a joke off a straight face, that McConville is one of the most popular GAA pundits in the business these days. We asked him the question that has been burning our lips since watching Sean Cavanagh's Laochra Gael last Thursday night. Would Dublin have six All-Irelands in a row if they were playing in the 2000s, against the likes of Tyrone, Armagh and Kerry?

"No I think they would have been nipped by one of the teams that you just mentioned there," says McConville.

"They obviously are a phenomenal team, but I do think, you can't really call it professional pride when talking about the GAA but I think those teams would have nipped them, not only was there too much quality in those teams, there was a nice blend of badness in those teams as well, that was able to break things down especially physically and I feel it would have been a lot more difficult at that stage, for Dublin to come in and dominate in the way that they have done.

"Not saying it's impossible, because they are phenomenal but it would have been a lot tougher."

If a lack of self awareness was his problem back then, McConville has come full circle now.

"I'm not sure if people want to listen to ex-gamblers, if you know what I mean. I'm thinking that they feel as if the message might be a bit skewed."

This message hits right down the middle. Just like his frees did, which is quite the achievement, given the demons he was battling throughout his playing career with Armagh and Crossmaglen Rangers.

"I enjoyed the responsibility. People around me didn't enjoy it, they were more nervous about what I was doing than I was.

"My Mum used to always say, 'Don't bother with the penalties.' She felt there was too much pressure with them.

"But I enjoyed that responsibility. I suppose I was very used to it and a coach told me something when I was about 14 or 15 which helped me. I was devastated after missing a free-kick and he just called me aside and said, 'Listen if you're going to take free-kicks, you have to realise that you're going to miss some," adds McConville, who works for Sporting Chance, an addiction foundation set up by Arsenal footballer Tony Adams.

With McConville, the war-stories, as he calls them, only become more and more engaging.

"We used to train in Armagh and there was a guy who used to turn the lights off at the end of the night whenever we were finished training. He used to blast them to get me off the pitch because I would be the last person.

"People used to think I was very diligent but my life was in a mess at that stage, and I hated getting back into the car because I knew I'd be going back to my normal life and the phone calls from people that I owed money to.

"A lot of the practice I was doing was just to stay out of that car because I didn't want that side of my life to continue on."

It's hardly any surprise, given his knack for cracking a joke off a straight face, that McConville is one of the most popular GAA pundits in the business these days. We asked him the question that has been burning our lips since watching Sean Cavanagh's Laochra Gael last Thursday night. Would Dublin have six All-Irelands in a row if they were playing in the 2000s, against the likes of Tyrone, Armagh and Kerry?

"No I think they would have been nipped by one of the teams that you just mentioned there," says McConville.

"They obviously are a phenomenal team, but I do think, you can't really call it professional pride when talking about the GAA but I think those teams would have nipped them, not only was there too much quality in those teams, there was a nice blend of badness in those teams as well, that was able to break things down especially physically and I feel it would have been a lot more difficult at that stage, for Dublin to come in and dominate in the way that they have done.

"Not saying it's impossible, because they are phenomenal but it would have been a lot tougher."

28 April 2021; Less than 1 percent of people who could benefit from treatment from problem gambling ever seek it. Extern Problem Gambling provides support for anyone affected by problem gambling and offers remote services by fully qualified and accredited addiction counsellors. If you or someone you know needs help with dealing with gambling, you can get help and support now by sending a text to Extern Problem Gambling on 089 241 5401 (ROI) or 07537142265 (NI). For more details, please visit: https://www.problemgambling.ie/. Former Armagh and Crossmaglen Rangers GAA player Oisin McConville in Crossmaglen during the Extern Problem Gambling Media Day. Photo by David Fitzgerald/Sportsfile[/caption]

28 April 2021; Less than 1 percent of people who could benefit from treatment from problem gambling ever seek it. Extern Problem Gambling provides support for anyone affected by problem gambling and offers remote services by fully qualified and accredited addiction counsellors. If you or someone you know needs help with dealing with gambling, you can get help and support now by sending a text to Extern Problem Gambling on 089 241 5401 (ROI) or 07537142265 (NI). For more details, please visit: https://www.problemgambling.ie/. Former Armagh and Crossmaglen Rangers GAA player Oisin McConville in Crossmaglen during the Extern Problem Gambling Media Day. Photo by David Fitzgerald/Sportsfile[/caption]Explore more on these topics: